Malaysian rapper Namewee is gleefully courting controversy and criticism with his especially bad CNY song for 2025. Really bad

Warning: The following contains language some may find vulgar, even offensive

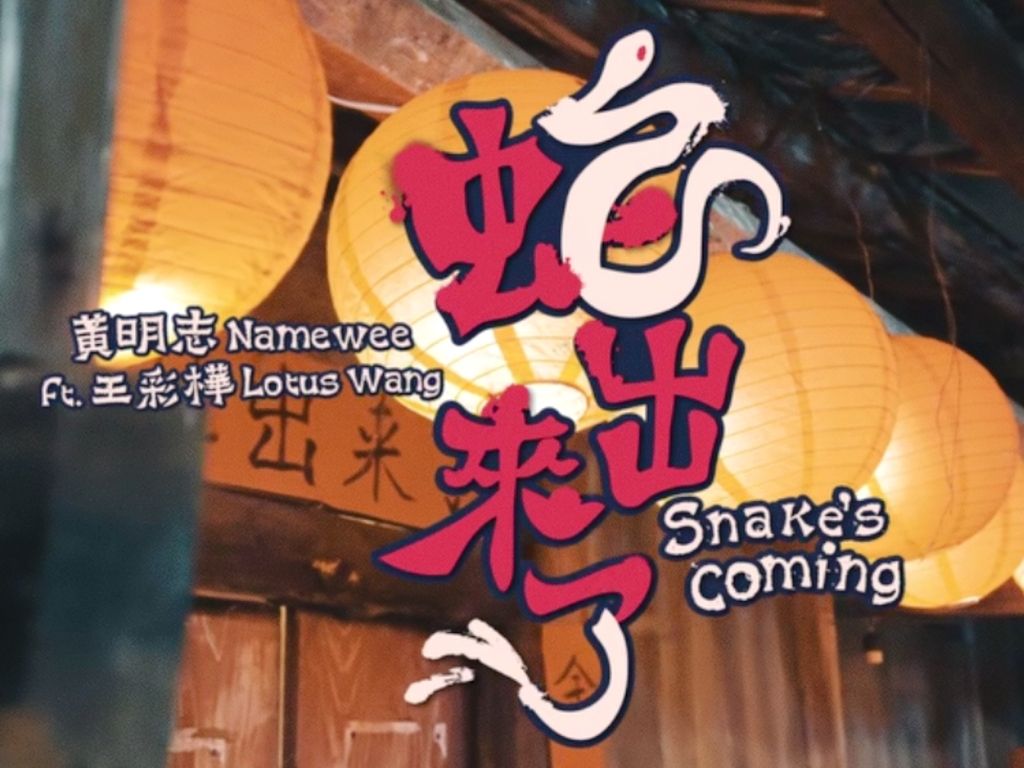

Christmas is not over, but in Malaysia, the mad rush to be the first to release Chinese New Year songs with the hope that they would become massively popular has commenced. One of the earliest performers to put out jingle-like tunes is Namewee (aka Wee Meng Chee, 黃明志 or Wang Mingzhi), the hip-hop artiste whose trademark is excess of cleverness and crassness. Released this past Saturday on his YouTube page, the song 蛇出来了 (she chu lai le or Snake’s Coming) has attracted close to 1 million views. If you thought his 2017 song for the year of the rooster, 那只鸡拜年 (na zhi ji bai nian or That Chicken Paying New Year Calls), with him alluding to prostitutes and both male and female private parts, was bad, this is far worse. We suspect that its appeal is not how refined the sound is or how clever the lyrics are or how artistic the MV is, but how vile and vulgar a CNY song can be.

CNY songs are not inherently examplar of sophisticated songwriting. But Mr Wee has taken his penchant for bad puns to a whole new level, and totally embraced grossness and indecency with the fervour of the depraved. The lunar calendar welcomes the snake at the start of the next spring festival (29 January). Rather than going into a slew of serpentine expression of auspiciousness, idiomatic or proverbial (along the lines of 祥蛇贺岁 or lucky year of the snake), Mr Wee, who is credited for the music and the lyrics of the song, chose the crude and the carnal. He used the word 蛇 (shé, meaning snake) in place of the homophone 射 (shè, meaning shoot or, when employed in a sexual context, ejaculate), but in phrases usually containing the latter and referring to male responses in coital success. The intelligent snake of the Chinese zodiac has come to suggest seminal discharge.

It does not require a filthy mind to see that his 蛇出来了 alludes to ejaculation—the act completed. His coarse chorus is replete with innuendoes: ejaculating—everywhere. “蛇在嘴巴 (she zai zui ba, or snake in the mouth)” is not as innocent as it sounds, and it gets progressively worse. Deliberate word placements, too, leave no doubt to what he is referring to: 莫名其妙就蛇出来了(mo ming qi miao jiu she chu lai) would have a different meaning if he had phrased it as 莫名其妙蛇就出来了 (mo ming qi miao she jiu chu la)—the latter is when a snake inexplicably appears. In addition, there is the problem in how he uses his supposed subject, the snake. It does not help that, like in the West, the Chinese do choose the snake to denote a man’s well-endowed member, just as Nicki Minaj has and we are in no doubt what she was referring to when she sang Anaconda. But in case that isn’t obvious enough, bananas, too, have a starring role in Mr Wee’s just-as-vile music video that accompanies the track.

His fans would no doubt call him clever, even 厉害 (lihai or amazing). Still, many more would consider his word play morally low. We doubt anyone is asking that he has to offer lyrics that appeal to the tastes of sophisticates. But lyrical attempts by way of the gutter means only one thing: you pick up the dregs. Mr Wee may think that he did not sing anything explicit, but there is nothing unambiguous about “snake on the wall (蛇在墙壁)” or “snake on cousin’s keyboard (蛇在表哥的键盘)”. Even the song title in English. He leaves little to the imagination: the ‘了’ character in the title graphically tails of with an appendage discharging. Or, is this to show some kind of hypermasculinity, a boast of the virility of the 爷们 (yemen) or menfolk? With the emphasis on the act of emission—essentially a male physical response—everywhere, why is this not sexual aggression? Or is he making a mockery out of the over-2,000-year-old Chinese zodiac even if he included the other animals in his lyrics? And why for Chinese New Year?

Eschewing the overt dong dong qiang-ness of typical CNY songs, Mr Wee’s arrangement includes the pungi, reed pipes that snake charmers typically use. In some scenes of the MV—filmed in Tainan (台南), Taiwan, he is even seen wearing turbans (and dressed like a shaman). It is hard not to consider this cultural appropriation even if the Muar-born rapper might think his instrument and fashion choices are reflective of multi-cultural Malaysia. But this is not Ah Niu promoting Malacca; this is about a celebration that goes back some 3,500 years, a celebration important to families. Mr Wee is also contributing to a tradition that is uniquely Malaysian—the race to release cheery CNY songs (especially among TV stations) to be played till one is numb to them; he is a veteran and he has to—must—do better, rather than let his questionable taste dictate, in full Beng glory.

It is known that Mr Wee loves to pun. Even his professional name is a play on the Mandarin pronunciation of his moniker, which sounds like 名字 (mingzi) or name. And he has this thing for homophones. From the start of his career, he toyed with them to full controversial effects. Many Malaysians would not forget one of his early singles, 2007’s Negarakuku, a regrettable mash-up that samples the Malaysian anthem Negaraku. His additional ku reference the Hokkien word for the male genetalia. The outrage is unsurprising. Yet it was never a deterrent to him, even after several detentions when Malaysian police looked into his alleged insults of state and religion. He was even banned in China, where his song 玻璃心 (bolixin) or Fragile was perceived to mock the Chinese government. But Wee Meng Chee, who faked his death in April to promote a music video, cannot resist provoking and he would not stop. As he told the South China Morning Post in 2018: “peaceful rap isn’t fun.”

Screen shots: namewee/YouTube

Congratulations ! You found a silly reason to get offended by.

LikeLike