Bad Bunny goes mass for the masses. And you can’t get more mass than the Super Bowl

Good Bad Bunny! How excellent of him to be dressed for clarity, not just the performance. At the Super Bowl Halftime Show, the Puerto Rican star truly surprised many when it was revealed that he wore Zara for his appearance at The Tactical Grass-Touching Festival. It was custom Zara, to boot. Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio took a brand that literally defines fast fashion and mass production, and had them stitch a one-of-a-kind ensemble for a set during what is one of the most-watched stages in the United States. Such a massive outbreak of attention he received that Turning Point USA had to compete with their own All-American Halftime Show. Charlie Kirk’s pony ride trying to out‑American the Super Bowl Halftime Show was like staging a backyard barbecue to compete with the Fourth of July fireworks—daft. TPUSA’s lame alternative with Kid Rock headlining felt less like patriotism and more like brand positioning, an attempt to claim ownership of “authentic America” by counter-programming against the most mainstream ritual imaginable. So, who gets to define American?

One singing and dancing Puerto Rican sure did, and entirely in Spanish. To augment that linguistic defiance, he did not choose American brands such as Ralph Lauren or Tommy Hilfiger, both known for their strident, flag‑draped Americana. His choice of Zara was both inspired and sly. Not only did he refuse to switch languages; he declined to costume himself in the predictable semiotics of American fashion patriotism—or cliché. By pairing Spanish lyrics with Zara’s cross-border appeal, he was underscoring a cosmopolitan America, one that could resist being boxed into myopic stars‑and‑stripes branding, and insisted, instead, that American identity is porous, multilingual, and globally dressed. Crucially, Zara embodies accessibility and ubiquity, qualities that the U.S., under the current administration, is distancing itself as it retreats explicitly from openness. Zara, by contrast, embodies the opposite: a refusal to tether identity to nationalism. ‘American’, to many outside the U.S., is succeeding as a static, closed-loop brand.

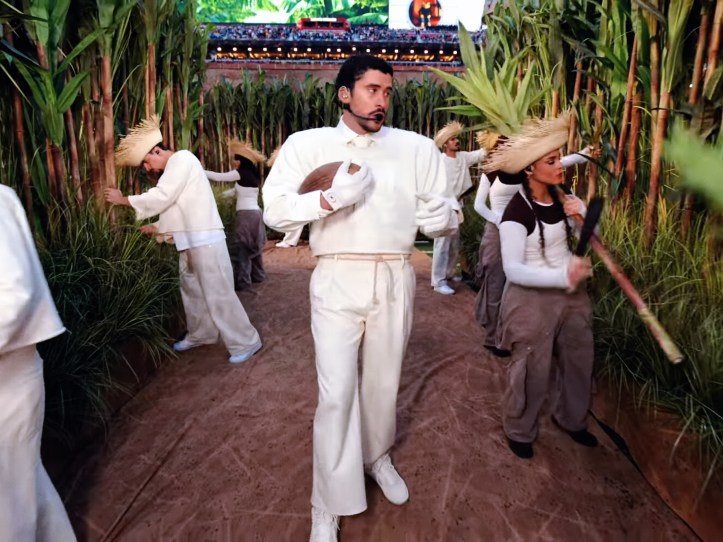

To kick off the show, Bad Bunny was, head to toe, in total paleness of buttermilk, serving vanilla ice cream realness, while singing Tití Me Preguntó (auntie asked me). The built-up of pale, right down to the gloves, would make a certain president’s Diet Coke nervous. It comprised of a shirt and a tie, both with the formality of school uniforms worn with scant love, under a loose-neck, three-quarter-sleeved, cropped pullover with the text Ocasio and the numerals 64 in the rear, as it would have appeared on a football jersey. There were initial rumours online that the name was direct endorsement of Democratic congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. But it was, in fact, the maiden name of the singer’s mother and 64 was the year of her birth. (Several reports have confirmed that 64 was also his late uncle’s football jersey number, while some suggest that the figure was the initial, widely disputed death toll reported by the government after Hurricane Maria in 2017.) Interestingly, that year, The Beatles vaulted to the top of the U.S singles chart for the first time with I Wanna Hold Your Hand, starting what was described as a “British Invasion”. No such invasion will be permissible now, but Bad Bunny was essentially saying he will hold hands!

While 1964 was an invasion of sound, 2026 is an integration of identity. He was not coming from over there since he was and is already here. A persistent rhetoric has weaponised “invasion” to frame migrants as perpetual outsiders and unwelcomed troublemakers. Adroitly, Bad Bunny flipped that script: he embodied belonging, not intrusion. He didn’t need to cross borders; he was performing from within, proof that Latin identity was already and still is central to U.S. plurality. His jersey was also a reminder of political reality: Puerto Rico is not a distant territory, but a part of America. The Latino Grammy winner’s presence, with Puerto Rican symbolism worked into his outfit and the set, collapsed the false boundary (wall?) between real Americans and others that have been evidenced by the many ICE raids throughout the country, some leading to deaths. Millions of viewers saw a jersey that looked like sports merchandise, but carried a coded critique of erasure and exclusion. The Bunny is not Bad at all.

But someone watching from the White House held a different view. The show got his diaper in a knot. In a lengthy review on Truth Social, he called it, “absolutely terrible” and an “affront to the Greatness of America”. His America is cast in the imagery of redwood trees—monuments of continental might, rooted in the mainland. Bad Bunny’s America, by contrast, is the tropical grass, sugar cane—hints of Puerto Rico’s colonial past, but now symbols of growth, and resilience that framed the opening of the show. The most telling part of his fuming was his insistence that “nobody understands a word this guy is saying”, never mind it was mostly singing. He also labeled the dancing “disgusting” for kids. Even the guest stars, such as Cardi B and Carol G, jiving were invited corruptors of children! A clear struggle with words when confronted with an America he doesn’t recognize or doesn’t want to acknowledge. There is something canny about not requiring to say a single word of English to make the most powerful man in the world feel like a benighted outsider at his own country’s biggest party, watched by, as reported, over 135 million viewers.

Midway through the set, during his performance with Lady Gaga, Bad Bunny swapped the jersey for a boxy, double-breasted cream blazer in homage of the salsero suit, a distant cousin of the American zoot suit (the wearing of it was once criminalised), both with histories of marginalised communities that used fashion as a form of visibility and protest. The costume change dramatised a shift from sports energy to cultural heritage. Even his guest’s fashion was part of the message. Lady Gaga wore a pleated dress with a three-tier skirt, custom-designed by Dominican-American Raul Lopez of Luar. She emerged not from a trapdoor, but from the center of a real-life wedding ceremony, which reframed the halftime show as a union, not a spectacle of separation. It was worlds joined in rhythm. As she launched into a salsa-drenched rendition of Die With a Smile, the message was clear: Lady Gaga wasn’t there to teach him English; she was there to follow his rhythm. Towards the end of the performance, when the stadium filled with the colours of two dozen nations, from Chile to Canada, the stage ceased to be a football field in California. It was a veritable living map, showing that the only thing more “disgusting” than Benito Antonio Martínez Ocasio’s dancing was one president’s inability to see that the border had already vanished.

Screen shots: nfl/YouTube