What was Malaysian influencer Ms Kuan doing at the recent Grammys and lived to announce with glee, “everyone is a winner?”

Christinna Kuan at the Grammys just three days ago. Photo: ms_kuan/Instagram

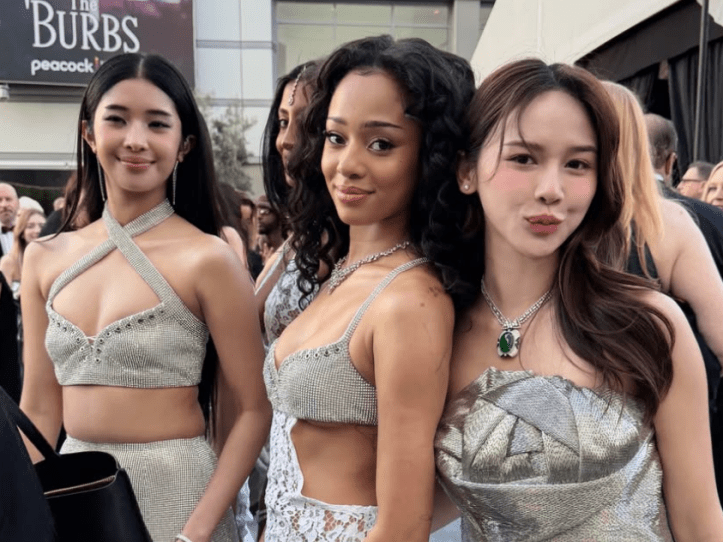

In the ICE-visible U.S., the red carpet is currently being unrolled at a rate that can be considered seasonal high. Standing on and strutting down one recently was Malaysian influencer Christinna Kuan (关丽婷 or Guan Liting), better known by the more formal Ms Kuan, with the addition of an honorific, as in the digitally-notorious Ms Piuyi. On 1 February, Ms Kuan was in Los Angeles to attend the Grammy Awards. One video that appeared on her socials has been keenly shared. It showed the Malaysian export at the award show. Dressed in a strapless, gold Oscar de la Renta dress with an origami bodice, she sailed through the crowd with the aimless grace of a lost tourist, looking very much like a woman who had misplaced her social circle and lacked the manual to start a new one. A column of glamour, adrift. The only persons she was photographed with were Manon Bannerman and Sophia Laforteza from the girl group and Best New Artist nominee KATSEYE. And, Miley Cyrus. Both shots appeared to be can-I-have-a-photo-with-you moments. Was she to them just another nameless face in the blur of a content creator circuit?

About a month before her debut at the Grammys, Ms Kuan appeared with her siblings, Jestinna and Perry, in a Chinese New Year ditty (song would be over-crediting it), Money Mari Mari (or ‘come come’). Like so many other influencers, the Kuan siblings joined the CNY ditty dump (they first appeared as high-decibel CNY noise pollutants in 2022), built on repetition, simple rhymes, and upbeat tempos designed for malls, TV ads, and reunion dinners so rowdy no one would pay attention to the ballistic karaoke. The Kuan kids’ balik kampong jingle is traditional, banking on both the cheerful and the communal. The video features a large cast, with the Kuans filling up the screen in cheesy costumes not even celebrants in Cheras would wear, successfully proving that money can buy an MV, but not a photogenic wardrobe. The trio didn’t so much perform as they negotiated their blocking and cues with the frantic enthusiasm of people reading IKEA furniture labels in a crowded showroom. In sum, Money Mari Mari thrives on overstatement and crassness, predictably turning Chinese New Year cheer into a boisterous parody of itself.

At the Grammys posing with (left) Manon Bannerman and (right) Sophia Laforteza. Photo: ms_kuan/YouTube

In January, she was the soundtrack to the aisles of Jaya Grocer (one of the sponsors of the video). In February, she was the Oscar de la Renta mannequin on the Grammys carpet. The influencer’s calendar was full. Money Mari Mari costumed her in polyester prosperity; Oscar de la Renta dressed her in reflected glory. Both were, as one marketing consultant noted, 粗俗 (cusu or crass) in their own way—one loud, one less, both empty. But one must admire how versatile Ms Kuan has been. She was singing with festive gusto “ma ma ma money” and, in four weeks, posing with the KATSEYE who chanted to fame, “hands off, Gabriela-la-la la-la-la-la”. Perhaps behind their smiles, they were silently shouting, “back off, Christinna-na-na na-na-na-na?” Ms Kuan posted numerous photos and reels of her night at the Grammys, but one burning question dominated social media: What was she doing there?

KATSEYE’s massive hit Gabriela is literally about someone trying to move in on territory that isn’t theirs—a main-attraction warning off a pretender. Irony rarely gets more delicious than this. By the traditional logic of the Grammys, Ms Kuan had no real reason to be there: she’s not an American recording artist, not a nominee, not a producer, not a songwriter, not a back-up, not a musician, not an industry executive. We can only surmise that she was a guest of a fashion house. Oscar de la Renta dressed her, which effectively gave her a ‘ticket’ to the carpet. She was there to flaunt a gown, not, as is usually the case, to participant in the music industry. But, music’s biggest night (as well as movie’s) is increasingly populated by people who have nothing to do with the industry. The Grammys have blurred their boundaries. They now host musicians, actors, fashion guests, and influencers—anyone who can amplify the spectacle beyond its broadcast audience.

Horsing around: Christinna Kuan (centre) with siblings Perry and Jestinna in the MV for Money Mari Mari. Screen shot: mskuanofficial/YouTube

Christinna Kuan is not, it should be noted, Siti Nurhaliza, who was invited by the Recording Academy in 2007 to attend the Grammys, where she was the first Malaysian to walk the red carpet, symbolically placing Malaysian music on the global stage. She was, crucially, invited as Malaysia’s most celebrated singer, one with over 300 awards, a solo concert at the Royal Albert Hall, and a career built on vocal mastery. Her presence—in Bernard Chandran—was a nod to her status as ‘The Voice of Asia’. In contrast, Ms Kuan’s appearance was the result of the influencer-brand economy. She was likely there as a guest of Oscar de la Renta or another luxury partner. She wasn’t breathing the rarified air because of a Record of the Year, but because she is a high-value marketing asset for brands wanting to reach the Southeast Asian luxury market. But what did Ms Kuan hoped to achieve with releasing Money Mari Mari before going to Los Angeles? So that she would be able to say to her fellow guests: “我是歌手 (woshi geshou), I am a singer”?

Social media’s obsession with her presence—the “what was she doing there?” of it all—isn’t just a matter of gatekeeping. It is a reaction to a profound national dissonance. As Ms Kuan’s self-congratulatory reels played out in loops, Malaysia is locked in negotiations over rare earth sovereignty, battling for exemptions in semiconductor and palm oil sectors, and generally operating in a defensive crouch against global economic pressures. Against this backdrop of economic friction, Ms Kuan’s girl-in-the-Grammys- glare isn’t just an influencer quirk, but a failure of representation. She wasn’t there to showcase Malaysian products except her co-owned jewellery line, rr.byrafflesia, in the form of a pendant-necklace (which paled in comparison to the “ICE Out” pins real artistes wear), but to benefit from the very trade of access that the peninsular’s industries are currently being taxed for.

Bejewelled and totally pleased, Ms Kuan en route to the Grammys. Photo: ms_kuan/Instagram

She is the ultimate ‘exempted’ export—a luxury by-product allowed into the U.S. duty-free, while back home, the rest of the country is locked in the high-stakes grind of the new global trade order. While trade figures have hit a historic high and the ringgit finally finds its footing, it hasn’t been easy. Malaysia has still to contend with 19% tariffs just to keep the doors to the American market open. It is not clear if she arrived in Los Angeles aware of this anomaly or America’s current policy against foreigners, or the overzealous actions of ICE officers that have certainly led to deaths, even if she wore the gown of an American designer as a shield. Her Grammys appearance is precisely the influencer archetype—someone used to maximising glee, spectacle, and circulation, while remaining ignorant of context, politics, or representation. We see only one explanation: prestige laundering. Although she is considered to be among the top-three of Malaysian fashion influencers, the ranking was not enough for her, given how cut-throat the competition is in the country. For an influencer dabbling in music, the Grammys are the ultimate shortcut to being seen as part of the entertainment ecosystem. It’s not about artistry, it’s about proximity to the spotlight. Jane Chuck, eat your heart out?

Ms Kuan’s reels and photos showed a turnout that represented the “American Dream” she consumed—expensive gown, red carpet, and high visibility, while the ICE actions represent the “American Reality” others are facing. But for some reason, she had to scratch the comeliness by anchoring one of her posts with a comment as nutritionally vacant as a stick of charcoal: “everyone’s a winner tonight”. If that was so, then the English language was in the last place. Her bumper-sticker comment was not just trite, it was a betrayal of context. It reduces the Grammys, ICE pins, Malaysia’s economic crouch, and the stakes of artistry into a meaningless platitude. Was she blind to the friction? Or did she simply choose the comfort of the blindfold? In the architecture of modern influence, context is the enemy of the vibe. Whether voice or vanity, both are vacuous. For Christinna Kuan, the red carpet isn’t a place of representation; it’s a green screen where she can project whatever reality her brand alignments command. Perhaps she didn’t ignore the world; she simply cropped it out.