A co-founder of Stoned & Co, a Malaysian brand that markets “unity”, found himself “relieved of management duties and authority” after a Ferrari-fueled display of plain, unadulterated road rage

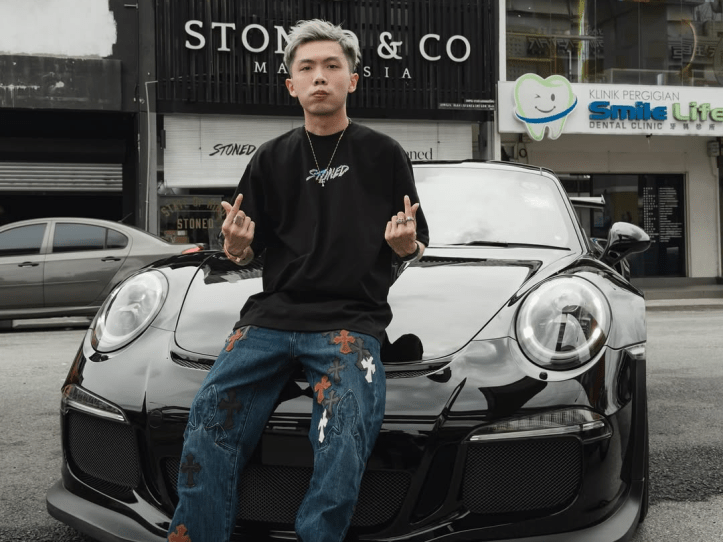

Tan Jia Hui seated on his Ferrari, outside his Stoned & Co store in Subang. It is not clear if this was the vehicle involved in the incident. Behind him is the site of his dangerous reaction to a honk. Photo: jiaahui/Instagram

He was standing in the middle of the road in front of the store he co-founded, Stoned & Co, his eyes glued to his phone. The man seemed unaware of the approaching vehicle behind him. The driver honked to alert the road hazard, and he took two steps to his right. As the vehicle past him, he shouted, “什么卵鸟 (shenme lanjiao)”, half Mandarin, half Hokkien phrase that roughly meant WTF, but with twice the vulgarity, as the male genitalia was referenced. The driver told him he was in the way. As he drove off, the self-styled lifestyle mogul taunted them: “来啦. 跑啦跑, 看谁快 (Laila. Paolapao, kanshuikuai)” or ‘come lah. Run lah run, see who’s faster’. In a matter of minutes, a Ferrari catches up with the first car, overtakes it, and halted directly in front, blocking the way. The other guy, got off his sports car, approached the driver, and shouted, but what he said was unclear. The first vehicle drove off, not wanting to provoke the visibly enraged chap. It is unknown if the Ferrari gave chase.

As it turned out, the man whose mouth operated on an un-filtered exhaust system was one of the three co-founders of the Subang-centred streetwear brand Stoned & Co, Tan Jia Hui. The incident apparently took place last December, two days after Christmas, but the dashcam footage was shared only in early January, sparking online outrage so intense that another co-founder Andrew Ngo had to go on Instagram yesterday to make a peace offering. Mr Ngo impressed his followers by telling them, in Malaysian Mandarin, that he has been through the ups and downs of 13 years of business life. Yet, it still pains him now that the reputation of his brand is tainted because of “一个人的行为 (yi ge ren de xing wei) or one person’s action and behavior. He did not mention Mr Tan, who ardently calls him “brother” on social media), by name.

The corporate divorce couldn’t be colder. It was announced that Mr Tan would be “relieved of management duties and authority”, but does that negate his involvement in the setting up and running of the business? “Management duties” are just a job description, while “ownership”, even if partly, is an identity. Mr Ngo’s statement is about operational control in the present tense. He was saying that Mr Tan no longer has decision-making power or day-to-day authority within Stoned & Co. It does not erase his historical role as co-founder, nor does it necessarily mean he has been severed from the brand entirely. This was reputation management; the brand wants to signal accountability without necessarily dismantling its founding structure. Saying “relieved of duties” is softer than “removed from the company”—it distances him from current operations, but neatly avoids the complexities of ownership and co-founder identity. They are, after all, best buddies.

When Mr Tan, in his Stoned & Co T-shirt and jeans appliquéd with Chrome Heart-style gothic crosses, stood there in front of his store and the black Ferrari as obstacle to vehicular traffic, what was he projecting? That SS15 was his grandfather’s road? Just because you’re in fashion does not mean you are blessed with style, sartorial or social. It was not hard to see, as so many have, that Mr Tan was a mannequin with a lease—trendy for the moment, ungraceful for the ages. The act of physically blocking traffic while togged in the brand’s identity projected a claim of territorial ownership, as if SS15 were an extension of his shop floor. To so many of the brand’s new-found critics, the act of blocking traffic suggested a claim of dominion. It was a performance of control, not of style. The irony is sharp: fashion is supposed to be about expression and connection, but here it became a display, even in the darkness of the night, for arrogance.

Andrew Ngo urging viewers to look past the recorded road rage drama. Screen shot: andrewngo23/Instagram

Tan Jia Hui together with Andrew Ngo, both former graphic designers, started Stoned and Co in 2014, the year Malaysia Airlines flight MH370 disappeared into thin air. According to their brand communique, there was a third co-founder, but that person has not been identified. The phantom final founder remains a footnote in their branding, perhaps the lucky one who exited before the ‘Peace and Unity’ mission statement became a punchline on a dashcam. For the most part, Mr Tan and Mr Ngo have been the faces of their label, enthusiastically promoting it on their respective socials. In Kuala Lumpur, where the brand is based, Stoned & Co is a recognisable homegrown streetwear label that is positioned as a pioneer in the local scene, but isn’t or more forward than those by other players dominating the market, including Pestle & Mortar Clothing (PMC), Against Lab, or Futuremade Studio (FTMD), a tech/outdoor-centric general label and store that would not be out of place in Tokyo’s Daikanyama.

To be sure, Stoned and Co has refined their products in recent years, but only to a modest extent. Yet, their offerings are good enough to entice Japan’s footwear retail chain Atmos (now part of the American retailer Foot Locker) to stock the Malaysian brand, specifically in their Bangkok store. How long this arrangement will last is not clear. The Atmos association may have amped up their street cred, but Tan Jia Hui’s street antics only confirmed what has been said about his brand for a long time: Stoned and Co was conceived by a trio of 啦啦仔 (lala zai), Malaysia’s answer to Ah Bengs, for the local Bengdom. Mr Tan is also sartorially Beng, just like his brand, which says they “always aim to create loud yet minimal style”. By acting out the road rage trope, the father of three essentially confirmed the public’s worst stereotypes about the brand’s leadership—that they weren’t creative visionaries, but rather lala zais who got lucky with a clothing line.

Tan Jia Hui is the perfect model for his brand’s unshakable ‘lala’ aesthetics. Photo: jiaahui/Instagram

The Ah Beng label has proven very difficult to shake, especially now that the brand’s “loud yet minimal” style has finally found its true expression in their hot-headed co-founder: loud in its aggression, and minimal in its integrity. On forums like Lowyat.net and Reddit Malaysia, Mr Tan, and by extension, Stoned & Co, is being used as a cautionary tale. It helps that its main store is right where the road rage struck. Subang Jaya, a suburban hub, is known for its student population, bubble tea culture, and streetwear enclaves. It’s vibrant, but it’s not Bukit Bintang. It’s more Sungei Wang in its heydays, but now witnessing the chaos and energy of the local student and streetwear culture. Rather like Bangkok’s Siam Square before it became gentrified. It is where bubble tea shops kept the company of vape stores. SS15 itself is a unique ecosystem where wealthy townies and business owners coexist with a massive, transient population of tertiary students. The road rage incident wasn’t just a random event; it happened in the exact place where those two worlds collide most aggressively.

There is notably a specific pride in being a budak Subang Jaya or Subang Jaya boy, however lala they might be, to the extent that local singer/rapper Joe Flizzow even sang about the particular breed in his 2016 song Havoc: Budak Subang Jaya memang ada gaya/Macam hari-hari Hari Raya (Boys of Subang Jaya certainly have style/as though everyday is hari raya). It became a full-fledged Budak Subang Jaya song, conceived with Sime Darby Property to promote the area. It is not known if Mr Tan is native to Subang, but his gaya isn’t alien to the place. Like those who buy his products, he has a weakness for massive logos, heavy typography (the Stoned branding), and high-contrast graphics. That’s the “loud”. He adopts simple silhouettes (oversized tees, hoodies, caps) as a canvas for that penjenamaan kuat (loud branding). That’s the “simple”. In Subang Jaya, you really can have your kuih and eat it too.

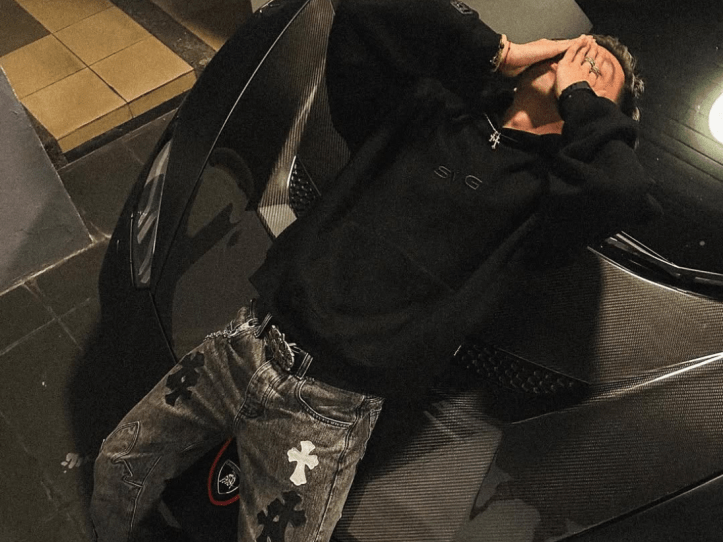

Again posing with an expensive car, this time a Lamborghini. Photo: jiaahui/Instagram

Another requirement of the lala aesthetic is the expensive sports car. Mr Tan has a taste for them and has been seen prominently—on Instagram—with a few from at least June last year, when he was photographed atop a chartreuse McLaren. It does not seem like he owns them. He could have been posing at a car showroom and, in some cases, probably taking a vehicle for a test drive. But his love for fast cars goes as far back as April 2012, pre-Stoned & Co, when he shared the first Instagram post of a speed demon, a yellow Lamborghini Aventador, a month after his very first IG post, featuring Cartier Trinity rings and a Love bracelet and a matching ring. As the video of the road rage went viral, social media discussions indicated that the Ferrari might not be his. Who would have thought that the high-speed temper tantrum exploded with borrowed horsepower?

For a brand named Stoned, its “main message revolves around peace and unity as the team wanted to instil positive notions to our diversified nation through fashion.” But one man’s ego-driven velocity is speeding a thirteen-year-old label to a destination—unknown. Perhaps, for Stoned & Co, the deepest irony was there from the start: their logo. It’s supposed to be the Japanese maple leaf, but could pass off as a cannabis palmate. It is a symbol that suggests zen-like serenity and attendant grace, yet it has been co-opted as the uniform for a brand of aggressive, lorong-level posturing. For years, Mr Tan and his bros have hidden behind this veneer of “peace and unity”, selling a collegiate cool that was as borrowed as the Ferrari he used to block traffic. But as the dust settles in SS15, the ‘Stone’ has proven to be less of a foundation and more of a sediment—the gritty, unwanted dregs left behind when the thrill of speed fades, just as the high of adrenaline dips and crashes. Tan Jia Hui may have been “relieved of his duties”, but the brand remains haunted by the image of one of its founders in the middle of the road, with his anger and his expletives. The power of a car horn.