When your “Hot Take” is a two-year-old grievance, you don’t drop truth bombs

As the year comes to an end, we’ve been reading some serious gripes over food establishments. Hard feelings don’t go away, we noticed. Bitter complaints are often stirred into a bowl of culinary evaluation. As one Stomp assistant editor showed two days ago, you don’t have to let a 2023 grudge over a serving of niangdoufu (酿豆腐 or yong tau foo) stay a private grievance; you can nurse it for a couple of years, and serve it back churlishly cold. Most people, when they haven’t visited a stall in 24 months, just call it moving on. She prefers returning to the stall in their final month of business for what she called a “last hurrah”, but instead of a rousing send-off, she delivered a sting: “longevity alone does not guarantee value—and perhaps not every closure deserves nostalgia.” Not everything worth keeping is optimal. Some things are just cherished.

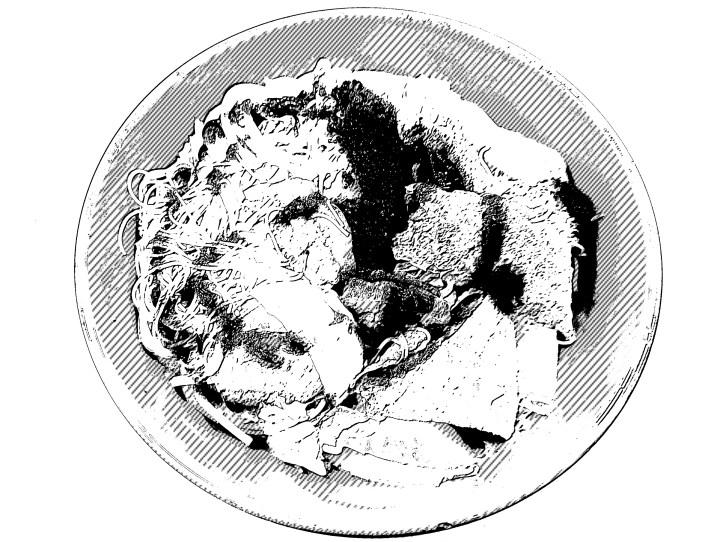

The object of her high-minded scorn is a Toa Payoh hawker stall 合衆客家酿豆腐 or Hup Chong Hakka Yong Tau Foo, whose pricing is, to her, extortionate, given that the business is in “a stuffy coffee shop in the heartlands”. Yet, for old-times’ sake, she had to revisit the stall, describe the offerings, and order a bowl of the cursed yong tau foo to eat that amounted to an indigestible S$9.20. While her ‘reaction piece’ (the textual equivalent of a YouTube reaction video—a retreat from expertise to ‘experience’) has a skimpy structure of a food review, it was devoid of taste notes. She offered no culinary evaluation, not even a whiff of connoisseurship, just the lingering scent of a desperate deadline. What fills the gap is axe to grind, an outpouring of the me at the expense of the meal.

She offered no culinary evaluation, not even a whiff of connoisseurship, just the lingering scent of a desperate deadline

She took a swipe at what the stall sells: “Don’t expect seafood or anything extraordinary though—by ‘premium’, the stall is referring to ultra-processed food infused with cheese and the like”. Seafood? And the subject is yong tau foo? Demanding seafood as a certificate of quality is a clumsy shorthand for a palate that hasn’t graduated past the surf-and-turf menu. Or, Long John Silver’s. By implying that only seafood counts as “premium”, she dismisses Hup Chong’s actual offerings. It’s a borrowed standard imposed on a tradition that doesn’t trade in lobster or prawns. Or is a paste of fresh ikan tenggiri (mackerel) or sai dou fish (西刀鱼, wolf herring) just not “seafood” enough because in the Hakka style of YTF, minced pork is mixed into the stuffing? Is this her culinary equivalent of the prohibition against wearing mixed fibres, as stated in the Old Testament’s Levitical law?

And there is the curious highlighting of the “ultra-processed food infused with cheese”. She does not say exactly what that fusion comestible is. We had to learn it from a Mothership report on the devastating effects that her revealing revisit exacted, specifically the emotional toll on the 80-year-old hawker. As it turns out, it is the lowly luncheon meat, molded minced pig carcass that turns up as an option to go with 菜饭 (caifan or cai png), 经济米粉 (jingji mifen or economy behoon), or nasi lemak, even Indian rojak. One wonders if luncheon meat in budae jjigae or Korean army stew is considered less processed and even worthy of a hunger-driven swallow since it’s mostly served in more atas restaurants. In all likelihood, even the cheese is processed since it unlikely artisanal cheddar or the like is used. She also noted that some of the items at Hup Chong are similar to those luxuriating in her fridge, including, ironically, processed meats, effectively saying I could get more food for less at home. With palpable glee she stated: “Regular ingredients include vegetables you can get for cheap at the supermarket, processed items such as hotdogs which I can find in my fridge, and fried food soaked in oil.” Should the world’s oldest profession—feeding people—be measured against her weekly FairPrice, possibly Fineness, run?

What boggles the mind, too, is the need to broaden the complaint to those around her. “Having braced myself before ordering,” she wrote, “I was not shocked when I was charged $9.20 for my meal—though my family and colleagues were when I told them.” She recruits her kinfolk and co-workers as a chorus: It’s not just me—everyone agrees this is outrageous. By invoking others, she inflates her gripe into a collective lament. It’s no longer one individual’s annoyance, but a supposed consensus. Even more inscrutable is how she knows the stall keepers so well: “It’s interesting that Hup Chong’s owner blamed competition in the area and work-from-home culture for a dip in business, but seemed to utterly lack self-reflection.” In her anthropological post-mortem, she elevates herself as arbiter of truth, as if she alone sees the “real” problem. She turns the stallholder’s words into a moral failing. She does not critique the business conditions, she judges the proprietor’s character. It is admirable that she accords herself the right to diagnose the owner’s supposed lack of introspection, delivering it on Christmas Eve—the ultimate season of grace. A rare talent indeed: in painting one portrait so vividly, she has, in fact, finished her own.

It is highly unusual for us to end the year with a piece on food. But given the recent rant on Rice Media, which framed a cultural discomfort with Chinese‑ness in food chains as a sociological critique, it is impossible to ignore the growing trend of leveraging grievance as a form of digital clickbait, even by the SPH-owned Stomp. One uses “ultra-processed” to describe luncheon meat, the other “sauerkraut” to describe 酸菜 (suancai or pickled vegetables)—linguistic gentrification to make traditional foods seem “cheap” or “wrong”. Both writers refuse to meet the ingredients on their own terms. Instead, they import alien categories to stage discontent. The stall or chain is cast as guilty of deception, while the writers pose as the enlightened unmaskers. Neither business is appraised on taste or craft, or tradition, but on how well it survives the reviewer’s personal, low-effort yardsticks—fridge inventories, culinary meritocracy, identity politics. The food guide becomes a stage for dissatisfaction, not deliciousness.

Illustrations: Just So