As the Miss Universe competition unfolds in Bangkok now, one very public dispute reveals how organiser Nawat Itsaragrisil’s cult of personality really ran the show

Nawat Itsaragrisil, chairman of the Miss Universe Thailand Host Committee. Photo:nawat.tv/Instagram

The Miss Universe pageant, or any other beauty pageant, is no doubt high-stakes theatre. It is emotionally charged, symbolically loaded, and logistically complex. This year in Bangkok, chairman of the Miss Universe Thailand Host Committee Nawat Itsaragrisil did not just participate in the expected drama; he amplified it, turning what could have been backstage tension into a full-blown public spectacle. The controversy erupted during the sashing ceremony yesterday, when Nawat Itsaragrisil—chairman of the Miss Universe Thailand Host Committee and CEO of Miss Grand International—publicly reprimanded Miss Mexico, Fátima Bosch, for not posting promotional content . The confrontation, broadcast live on social media, escalated as Ms Bosch was asked to leave the venue, prompting several contestants to walk out in solidarity.

Mr Itsaragrisil confronted Ms Bosch live, accusing her of disrespecting sponsors and disrupting the event. Videos that have been circulating online showed the former performing like a throne-holder and berating Ms Bosch about her absence from a sponsor photoshoot. During the heated exchange, a doggedly-offended Itsaragrisil directly questioned her intelligence, saying, “If you follow the order from your national director, you are a dumb head.” When she tried to say something, he told her: “I didn’t give you the opportunity to talk.” Refusing to let he voice be heard, he angrily called for security to have her removed from what looked like ballroom where the contestants had gathered for an “orientation”, dressed as if they were attending a state dinner. Ms Bosch walked out of the event in protest. But he told her to stop, even telling staffers in Thai to shut the door. Several other contestants, including the reigning Miss Universe, Victoria Kjær Theilvig, followed in a show of solidarity.

Miss Mexico Fátima Bosch speaking to the media after the squabble. Screen shot: 10newsau/Instagram

Outside the ballroom, Ms Bosch, in a green bustier-gown and sashed, told local reporters (and we quote verbatim), “what your director did is not respectful. He called me dumb because he has problems with the organisation… He said to me shut up and a lot of different things and I think the world needs to see this, because we are empowered woman and this platform is for our voice. No one can shut our voice. No one will do that to me.” Miss Mexico looked posed, confident, totally unfrazzled in the impromptu press statement that turned the host country’s aggression into a rallying cry. It wasn’t polished; it was raw, urgent, and real. When she finished talking, the audience gave her a rousing cheer.

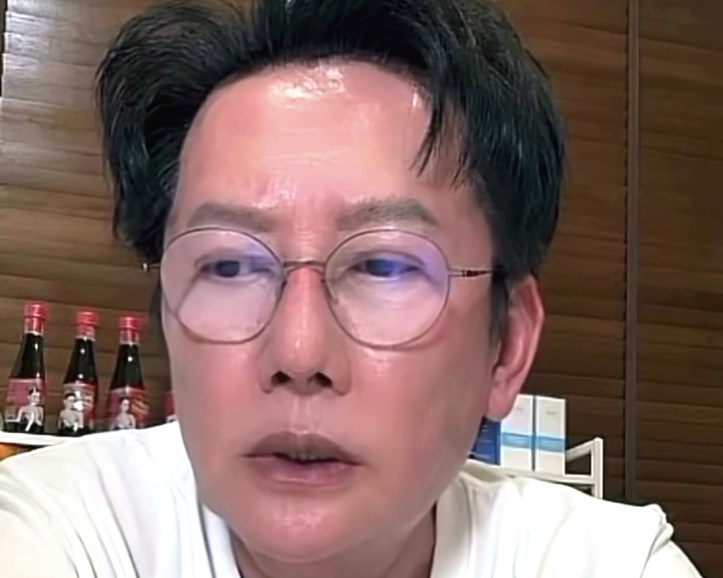

The incident quickly went viral. Mr Itsaragrisil issued a public apology via Instagram Live, though he didn’t name Bosch directly. Dressed in a white T-shirt with an eight-point star on the chest and filmed in what looks like a kitchen (there were bottles of sauces behind him), he went about in his Thai-accented English, framing the blame as frustration over contestants refusing to film sponsor videos, not so subtly shifting the narrative from his own behavior to theirs. This deflection suggests he was trying to justify his outburst rather than own it. Not directly mentioning Ms Bosch, Nawat sidestepped personal accountability. This tactic was an attempt to minimize legal or reputational fallout while still appearing conciliatory. His tone lacked warmth or humility. He sounded like a teacher choosing self-defence, framing the scolding of children to humiliate them as a necessary defense of his authority; he was more concerned with optics than reconciliation.

Nawat Itsaragrisil apologising to anyone who cared to listen. Screen shot: TikTok

The discourse devolved so quickly that Miss Universe Organization (MUO), President Raul Rocha, came out to say “you need to stop”! The moment was a rare and pointed intervention that underscored the severity of the conflict erupting behind the scenes in Bangkok. Mr Rocha released his own video that did not look like it was shot in a kitchen, expressing in Spanish solidarity with the 122 delegates, emphasizing their dignity and safety. He condemned Mr Nawat’s behavior, saying he had “forgotten the true meaning of what it means to be a genuine host.” Mr Rocha is Mexican, as is Fátima Bosch. The rebuke was public and official, signaling that MUO was reclaiming control from a host partner who had overstepped. His “you need to stop” wasn’t just disciplinary, it was declarative. A clear line in the sand.

Most damning was Mr Bocha expressing his true feelings of Nawat Itsaragrisil, saying the Thai co-partner has a “constant desire to be the centre of attention.” This could be new to the rest of the world, but in Bangkok, many people involved in the pageant and entertainment business are well aware of Mr Itsaragrisil’s hunger for stardom—the spotlight is his only career goal. This looks unmistakably like narcissism with a business plan. His entire public persona is a hyper-curated blend of pageant theatrics, influencer bravado, and patriarchal control masquerading as glamour. Some say “matriarchal”, given his dowager attitude and temper. It’s his power costume. And it goes with the grandiosity, the melodrama, the ceremonial scolding. The decisive, formal blow to Mr Itsaragrisil’s power play was delivered when Mr Rocha announced that his Thai partner’s responsibilities would be restricted: “limiting it as much as possible or eliminating it entirely”.

Miss Universe Organization President Raul Rocha. Screen shot: missuniverse/Facebook

Unlike former co-owner of Miss Universe, Donald Trump, who wanted to be part of it because he got to socialise with beauty queens, Mr Itsaragrisil performs as if he is one. One, a backstage mogul, the other, front-stage diva. Unverified chatter points to Mr Itsaragrisil living vicariously through the contests because of an unfulfilled dream. His intense focus on how contestants walk, speak, dress, and obey suggests a desire to sculpt idealised versions of himself, as if each queen is a proxy for his own unrealized self-image. While he frames his dream as creating a successful historical event, many in the Thai pageant business interpret this intense focus on the contestants’ compliance and appearance as a displaced personal ambition. This cuts to the symbolic heart of Mr Itsaragrisil’s pageant empire. He, as one Thai event organiser told us, “doesn’t want to crown beauty; he wants to be the crown.”

Nawat Itsaragrisil was born in 1965 in Damnoen Saduak, Ratchaburi province. He attended the University of the Thai Chamber of Commerce, where he graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in Economics. His professional career really began in television, where he hosted travel shows like Exhibition Show and Today Show. Television was a stepping stone to the pageant world and in 2007, served as the director and executive producer of the Miss Thailand World pageant for the next five years. In 2013, he founded his own major franchise, the Miss Grand International (MGI) organization. His influence in the global pageant world expanded significantly in 2025 when he acquired the license to run Miss Universe Thailand and was appointed an executive director of the Miss Universe Organization.

Mr Itsaragrisil, centre, who loves to pose with beauty queens, with some of the MU contestants days ago. Photo: nawat.tv/Instagram

When we tried to understand Nawat Itsaragrisil’s real role in the MU universe, we were met with a very complicated organisational story. It is highly intertwined and complex as it stems from Mr Itsaragrisil’s leadership in multiple, sometimes competing, organisations. The Miss Universe Organization’s arrangement with him began as a strategic partnership: He is already president of Miss Grand International and national director for Miss Universe Thailand. In April this year, he was appointed MUO’s executive director to help oversee global operations and host logistics. This move was controversial, given his long-standing rivalry with Miss Universe and his reputation for theatrical control. Mr Itsaragrisil had always been unapologetically vocal about rivaling the Miss Universe contest and plotting to dislodge it from its top position. He even called MGI “the future of beauty pageants”.

The irony now is unmissable. Despite years of rivalry, many thought that MUO’s willingness to work with him was as an attempt to co-opt or neutralize his influence. But the Bangkok scandal proved that his loyalty to MUO was always conditional, and his instinct to dominate, not collaborate, ultimately backfired. He wants to redefine what global beauty looks like, on his terms. He sees MUO’s values—dignity, diplomacy, diversity—as soft power veneers, while he champions raw spectacle and loyalty. His endgame, some are now saying, isn’t just to rival Miss Universe, it’s to replace it as the symbolic center of global pageantry. But there is another curious point. Mr Itsaragrisil replaced Anne Jakrajutatip as executive director of the MUO, following her resignation amid a financial scandal involving Thailand’s Securities and Exchange Commission. His appointment was part of a broader leadership shake-up that set the stage for the Bangkok controversy.

Anne Jakrajutatip, the controversial predecessor of Nawat Itsaragrisil. Photo: annejkn.official/Instagram

Ms Jakrajutatip, a Thai media mogul and transgender business icon, purchased MUO in 2022 through her company JKN Global Group, becoming the first woman to own the pageant. Her tenure was marked by multiple scandals, including financial misconduct, controversial statements, and internal instability. In early 2024, a video surfaced, allegedly showing her dismissing MUO’s inclusivity efforts as merely a “communication strategy”, undermining her public stance on diversity and empowerment. Her leadership saw frequent changes in national franchises, unclear contestant eligibility rules, and accusations of favoritism, which eroded trust among pageant directors and fans. While she positioned herself as a trailblazing transgender CEO championing equality, insiders described her management style as erratic and overly centralized, with decisions often made unilaterally. Both the oversight of Nawat Itsaragrisil and his predecessor Anne Jakrajutatip show that Thailand’s pageant infrastructure, while visually spectacular, has become a flashpoint for overreach.

More importantly, it is adding salt to the wound of Thailand itself mired in scandals that have turned tourists away. The Miss Universe Bangkok unscheduled revelations didn’t just expose dysfunction within pageantry, it echoed Thailand’s broader crisis of image, trust, and international perception. When Mr Itsaragrisil publicly humiliated Miss Mexico, and the fallout went viral, it wasn’t just a pageant problem, it became a metaphor for a nation struggling to reconcile spectacle with substance. Miss Universe was supposed to be Thailand’s soft power showcase, a glittering event to reaffirm its global hospitality and cultural grace. Instead, the host director became the antagonist. The ballroom became a battleground. Nawat Itsaragrisil has always wanted international fame. Now, he got it.

Update: 5 November 2025, 18:30

Nawat Itsaragrisil bawling uncontrollably at a press conference. Screen shot: TikTok

Videos circulating on TikTok showed Nawat Itsaragrisil apologise easier, during what looks like a press conference, He began, saying, “It’s (sic) a lot of things happen (sic) to me.” Right at the top, he instantly reframed the scandal as his personal hardship, not the harm done to Miss Mexico or the delegates. Classic drama queen deflection.

He went on to state that “it’s very hard to control our group to move on forward (sic) all the time.” What has that got to do with anything he did not say. He went on: “I am the human. I didn’t want to do anything like that, but I cannot clear myself and my team and the delegates and we stuck for the our sponsor all the time.” By this time, it was hard not to assume that Mr Itsaragrisil had too much to drink. The rest of what he said was incomprehensible. He ended by denying that he called Miss Mexico, Fátima Bosch, “dumb head”, claiming he said, “damn it” before changing it to “damage”.

In another similar video, Mr Itsaragrisil spoke in Thai, explaining the investment that he has made—“over two million in cash”—and bawled, tearlessly. In this second part of his apology, he claimed the role of victim, despite being the aggressor. He performed vulnerability, but without surrendering control. He used apology as spectacle, not as repair. It’s the classic emperor dowager act: dry-eye wailing, ceremonial grievance, and self-crowning through suffering. When the stage is built for sympathy, the truth rarely gets the mic.