It seems Malaysian rapper Namewee’s commitment to social justice paused for a cocktail of illegal drugs, tragically revealed after a party turned fatal. Now, the police has issued a warrant for his arrest in connection with that death

Namewee promoting the whiskey brand JF Dominic on his Instagram page. Screen shot: namewee/Instagram

This has the makings of Malaysia’s own hip-hop fall from grace, the classic unravelling narrative seen across the global rap scene. It’s a familiar story of artists building whole careers on rebellion and charisma, only to be undone by the very chaos they courted. On 22 October, Wee Meng Chee (黃明志, Wang Mingzhi), popularly known as Namewee, was arrested in an unnamed Kuala Lumpur hotel room after police discovered what they thought were Ecstasy pills. Crucially, his urine tested positive for multiple illicit drugs, including amphetamines, methamphetamine, ketamine, and THC (tetrahydrocannabinol, a cannabinoid found in cannabis). He was incarcerated for two days and, this afternoon, was charged with drug offences. Mr Wee pleaded not guilty and was granted bail of RM4,000 (about S$1,242) with one local surety.

A day earlier, the rapper shared on his Instagram page a text-post of what appeared to be a rebuttal against not only the charges against him, but the online chatter about his possible guilt. It was characteristically defiant. Writing in Chinese, he said: “I saw another piece of news that was based on 捕風捉影 (bufeng zhuoying or unsubstantiated claims) and I feel very dulan (using the anglicised version of the Hokkien expletive that means pissed off).” He went on to paint a picture of wronged virtue. “I did not take drugs, nor did I carry drugs. At most, I’ve been drinking more recently. Those who believe me will believe me; those who don’t, won’t. In any case, the police report will allow 水落石出 (shuiluo shichu or reveal the truth). This should take another two or three months.”

The rapper shared on his Instagram page a text-post of what appeared to be a rebuttal against not only the charges against him, but the online chatter about his possible guilt

Just as his social causes tend to be performative, this was as much a masterclass in a retort that sounds emotionally charged, but is semantically the equivalent of Styrofoam. Sure, it is a symbolic show of innocence pulled together to signal, but what it signals is defiance, not transparency. He describes the online chatter as 捕風捉影 (bufeng zhuoying), baseless gossip. But it’s a sleight of hand for it doesn’t address the toxicology report, the charges, or the circumstantial evidence. It reframes the issue as persecution by rumour, not evidence of wrongdoing. He uses dulan as a sort of folk-hero fury, tapping into a specific cultural register: the angry, working-class everyman wronged by elites.

The most revealing line is: “Those who believe me will believe me…”, an epistemic shrug, a deliberate choice of soft focus. This is hardly a defence. He’s not trying to persuade; he’s drawing a line between believers and doubters. It’s a loyalty test, not a truth claim. And his fans fell for it. Despite the positive urine test, he doesn’t explain the results. He doesn’t challenge the science. He just asserts innocence and wishes to move on. This post isn’t about facts. It’s about preserving the myth of Namewee. He, the misunderstood rebel, the folk hero under siege, the man too real for the system. It’s a performance for his base, not a reckoning with the charges.

Iris Hsieh in an IG post dated 29 September 2025. Screen shot: irisirisss900/Instagram

The incident is also linked to the sudden passing of Iris Hsieh Yu Hsin (谢宥芯), a Taiwanese influencer, dubbed the 護理女神 (huli nushen) or nurse goddess, found dead in the bathtub of the same Kuala Lumpur hotel where Mr Wee was also staying at the time. The proximity of their rooms—and the timing of her death—has led to intense speculation, amplified by the media and public imagination. Initially, Ms Hsieh’s death was reported as a sudden heart attack. Her manager confirmed this, and early reports suggested a tragic, but natural passing. Now, Kuala Lumpur police reclassified the case as murder under Section 302 of the Penal Code, citing “new evidence”. While Namewee has not been charged with homicide, his proximity to the scene—and the timing of his drug charges—has intensified public scrutiny.

This reclassification transforms the incident from a tragic coincidence into a potential criminal nexus. Even if Mr Wee is not legally implicated, the stain is set. While the heart attack narrative offers a clean break, the murder classification invited speculations, conspiracy theories, moral panic, and now, warrant for his arrest. Apparently, Mr Wee cannot be be found. The KL police chief Fadil Masus told the media: “We have not been able to locate him; we believe he has gone into hiding.” The defiant has disappeared. In staying out of sight, might Mr Wee be trying to control the narrative through social media rather than being seen in handcuffs or courtrooms? But flight implies guilt, or at least fear. It undermines his Instagram rebuttal and defiant tone, turning him from a rebel to a fugitive.

Namewee in his reality show Namewee Money Game. Screen shot: namewee/Instagram

Mr Wee’s career has always been a tightrope walk between satirical genius and jail time. His controversy stew is so 浓 (nomg) or intense that Hong Kong stars actively distance themselves from him after the curtains were pulled back. After years of successfully avoiding arrests for national anthem parodies, religious jabs, sexual innuendos, and China-baiting, turning them into viral content, the Malaysian rapper is now facing something that can’t be spun or punned as a social commentary: a murder probe linked to the death of a Taiwanese influencer. His sudden, highly-publicised disappearance after being released on bail for his new, decidedly less artistic charge of drug use suggests his typical rebellious bravado has run out of performance space. It seems the man who made a career of criticising a flawed system is now running from it, proving that the line between “irreverent rebel” and “police fugitive” is startlingly thin, and the stakes are no longer just album sales.

Can artistic rebellion coexist with personal responsibility. Namewee’s artistic bravado has always been about pushing boundaries: confronting racial taboos, mocking authority, and embracing vulgarity as a form of satire. His provocations feel like a deliberate challenge to societal norms. But when drug use enters the picture—especially in a case tied to a tragic death—it shifts the narrative from symbolic rebellion to real-world recklessness. What was once thought as fearless expression now risks being seen as self-sabotage. For many of his fans, that’s the heartbreak of watching an artist blur the line between performance and reality—until the consequences are no longer metaphorical.

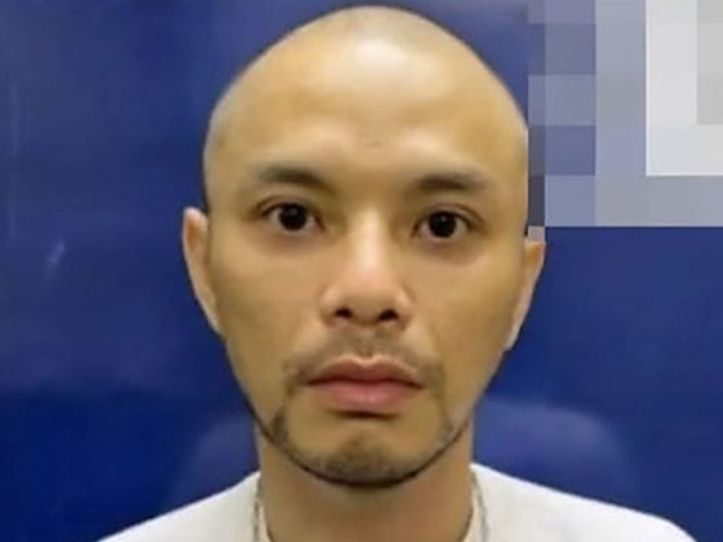

The police mugshot that has been doing social media rounds. Screen shot: missingvivian/Instagram

The idea that suffering or rebellion must be fueled by substance use is a damaging myth. Many artists, activists, and thinkers have made profound contributions to society while living disciplined, sober lives. Integrity, empathy, and courage don’t require chemical enhancement, only clarity, conviction, and resilience. Mr Wee’s work has spotlighted racial tensions, censorship, and hypocrisy in Malaysia (issues that deserve serious attention), but when the messenger becomes mired in scandal, the message loses its power. Social justice demands accountability—not just from systems, but from those who claim to challenge them. If the artist loses credibility, the art loses impact.

In a mugshot that was released to the media, Wee Meng Chee was seen without his signature beanie, essentially the ultimate forced unmasking. What was visible was really not: the hairline. The 42-year-old seems to be suffering from alopecia, otherwise known as male pattern baldness, in its rather advanced stage. It now appears that the guy has a far simpler, more relatable secret hiding underneath beanies and such. For a celebrity whose carefully curated rebel image relies heavily on youthful, anti-establishment male energy, being publicly exposed not just to the authorities, but to a ready audience for a receding hairline is a profound, if darkly humorous, layer of vulnerability. The police finally got him on a serious charge, but everyone else got him on his hair. It’s the ultimate poetic justice in pop culture. And the controversial artist’s biggest controversy? The mirror, or camera lens, always wins.

Updated (4 November, 19:00) to include information about the warrant for the arrest of Wee Meng Chee

Update (5 November 08:30): Wee Meng Chee has resurfaced! Seven hours ago, he shared a text-post written in Chinese on Instagram Stories to state that he “不会逃” (buhuitao, will not flee) after strong public suspicion that he has fled following the police announcement that he could not be found. He claimed that he had just returned to Kuala Lumpur from Johor Bahru, and stated: “Earlier, I had already scheduled a time with the police to go to the police station to file a report and check in. I have now arrived at the police station. Next, I will fully cooperate with the police investigation to provide a clear explanation to the public and the family of the deceased.” Additionally, he declared: with “the previous seven warrants, they were all instances where I voluntarily reported to the police myself; I have never run away.” Wee Meng Chee has re-entered the narrative—not as a man in hiding, but as a self-styled responsible citizen.

The post was accompanied by a short reel of himself in front of what is thought to be a police station. The image is classic, recognisably Namewee: beanie, T-shirt, and posture of resistance. Even in surrender, he performs control, acts cool. As usual, there is something theatrical about his re-emergence. It is all part of a visual and rhetorical script directed for his IG audience. One of his fans commented on his post: “勇敢的面對一切,真男人” or facing everything bravely, a true man. Another sold. What Wee Meng Chee posted is not just a statement. It’s a strategic re-entry into the narrative. The timing is surgical: just after the arrest warrant, just before the media could fully define him as a fugitive. It’s a move to restore his folk-hero standing, to pivot from hunted to helpful. This is not meek surrender; this is narrative gongfu.