The Miss Universe pageant is near. And this year, our island’s national costume will again bring the ethnic motif potluck to the world party

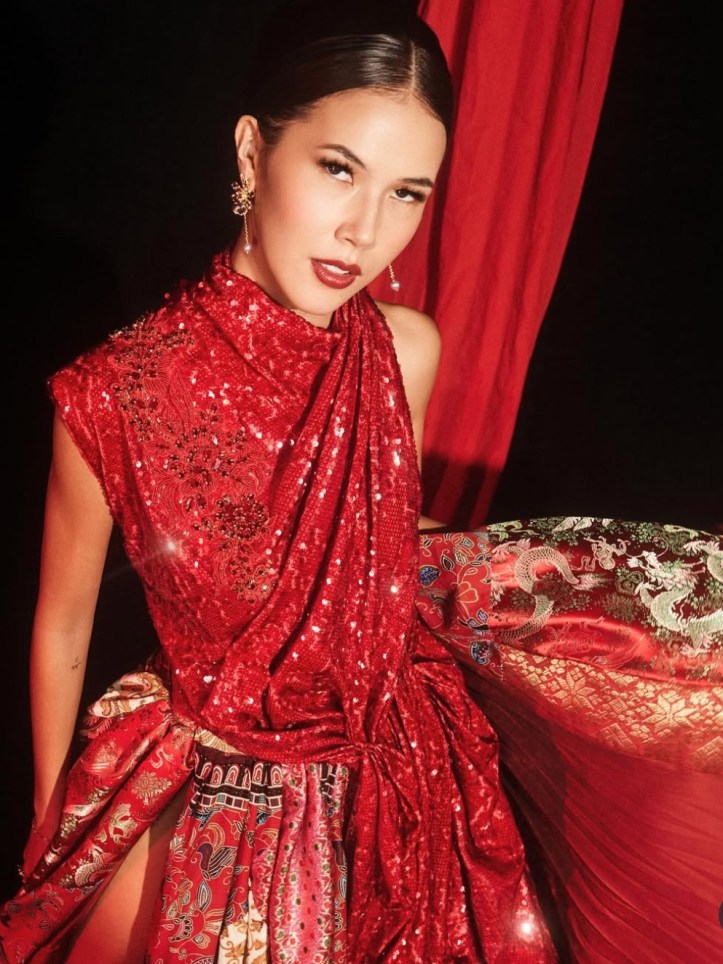

Annika Xue Sager in the national costume she shall be wearing

The Miss Universe pageant, an annual quest for world peace, is here again. This year, Annika Xue Sager, crowned Miss Universe Singapore 2025, shall show in Bangkok next month that this is the best we can do as cultural ambassador. For the National Costume segment of the competition, she shall be wearing a red, seemingly two-piece outfit designed by one Josiah Chua, who identifies as a “Fashion Styling/Creative + Art Alchemist”, according to his Instagram profile. They are big descriptions, but there is no mention of him as a fashion designer. This year’s costume tenaciously reaffirms the same tropes of past years, once again drawing from our four official racial groups—Chinese, Malay, Indian, and Eurasian—this time draped in more SG60 symbolism.

The gown appears to be composed of two parts: The upper which is an asymmetric, sleeveless, draped top with an oddly high collar and the full floor-length skirt composed of vertical panels of different ethnic fabrics, such as the batik, the Chinese brocade, and sari resham. From the photos supplied by Miss Universe Singapore, it is unclear what is used to represent the Eurasians. But it is clearly national unity craft. The blouse seems to be a mash-up of pallu (the decorative end piece of the sari fabric that is typically draped over the left shoulder) and a Western-style shell top. And the skirt is conceived as a sort-of-lehenga, but isn’t quite as voluminous—just sufficiently constricted to warrant a very high slit, in case Ms Xue Sager needs to strut sexily. As Taylor Swift would identity, there has always been the showgirl antics about the pageant.

the skirt is conceived as a sort-of-lehenga, but isn’t quite as voluminous—just sufficiently constricted to warrant a very high slit, in case Ms Xue Sager needs to strut sexily

The MU pageant for the Singapore participants has always been a showy tribute to unity in diversity. This approach—reiterating the racial harmony narrative through textile symbolism—has become a familiar formula in Singapore’s national costume strategy. While it’s visually striking and politically safe, it rarely ventures into more nuanced or provocative territory. The repetition of this motif (and the like) year after year feels like a symbolic loop: heritage as static display rather than evolving dialogue. Just because the Merlion does not tire from spouting water from its mouth does not mean we will never be jelak (tired/satiated) of the kains (clothes) of familiarity or the need to remind the world that we are such a beautifully harmonious nation that we always strike the chord that avoids all dissonance. If the idea of marrying the aesthetics of different ethnic groups into one garment for the Miss Universe pageant is not yet a cliche, it is because the idea is institutionally protected

Cross-cultural pollination in dress is nothing new when we look back at what we have worn. The Peranakans are a prime example of cultural fusion, and their wardrobes filed that report, too, and strikingly. Their amalgam of Chinese embroidery, Malay silhouettes, European lace all weave into a lived aesthetic of hybridity. But what makes it powerful isn’t just the vivid mix—it is the intimacy of that mix. These garments aren’t designed to perform multiculturalism for a global audience; they are worn in kitchens, at birthdays, at weddings, and during the lunar new year. They carry emotional residue, not just symbolic intent. Miss Universe Singapore 2016 Cheryl Chou’s costume by Moe Kasim embodied that regret. In a pageant setting, it is hard to decide when such hybridisation is emotional inheritance or just visual asset.

Blouse meets skirt and the very high slit

Our own ideas of national costume, it seems, must be laundered in metaphors before it can be worn. After all, they have nothing to do with a fusion that is organic and cultural, but a mélange more curated and artificial. The reluctance to evolve is possibly the costume’s most significant failing. Singapore is celebrated globally not for its traditional textiles, which are shared across the region, but for the audacious engineering of its urban infrastructure and life, as well as its status as a technological nexus. We do not look into the choreography of urbanity that’s as masterminded as it is elegant, even pretty (except for the Super Tree of 2017, again designed by Mr Kasim). Rather, we retreat into the safety of multiculturalism. What if the national costume reflect the actual spectacle of/that is Singapore?

If pageant costumes are built for spectacle, Josiah Chua’s gown is somewhat prosaic. It not only completely lacks the expected wow factor, it feels like it forgot there was a wow factor to begin with. The blouse is messy, the skirt looks deflated—a curtain of mixed fabrics, panelled like home-made Chinese New Year lanterns, drawn at the waist, and, in sum, appeared more like the day after. The “SG60” theme has potential for futurist flair or infrastructural drama. Instead, we got a hongbao ensemble that looks like it has been through a long National Day parade and needed electrolytes. What Mr Chia aimed for is diplomacy through cloth—safe and legible, but with zero emotional wattage. When will we move beyond ancestry to express audacity? Or are we happy to have a costume that doesn’t ask what it means to be Singaporean now, but just reaffirm what it meant in 1965?

Photo: Jeff Chang/Miss Universe Singapore