Viewpoint | No cynicism, please. They Are Vogue (Singapore)

Vogue SG’s Desmond Lim, in sunglasses, fourth from the left, at the recent ‘Next in Vogue’. Photo: monkiepoo/Instagram

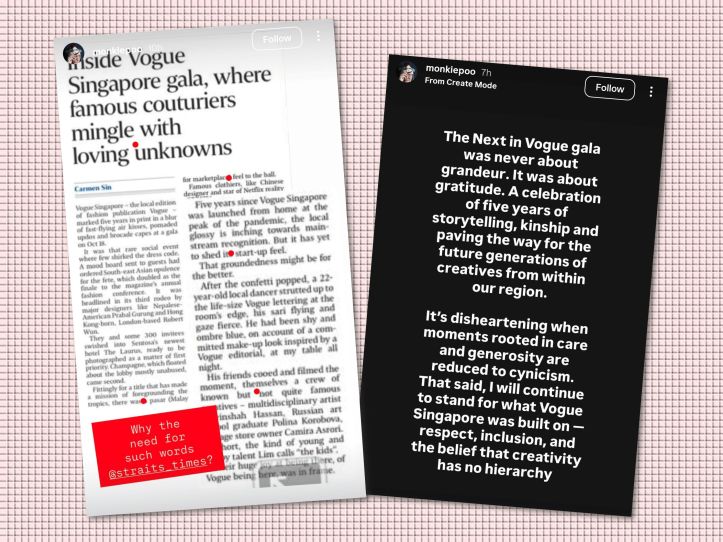

Yesterday, about ten hours after the Vogue World: Hollywood show in Los Angeles ended, the editor-in-chief of the Singapore edition of Vogue, Desmond Lim, shared on his personal Instagram Stories apparent dismay with a report in The Straits Times about the ‘Next in Vogue’ gala he had proudly hosted nine days earlier. The ST editorial appeared on 23 October and offered what we thought was revealing insight into the event, but apparently not to Mr Lim. He must have had four harrowing nights of tossing and turning before he emerged from his emotional chrysalis to deliver a heartfelt post on IG Stories. Somewhere between the third chamomile tea and the twelfth re-read of the ST article, he could have realised: the world simply didn’t understand his hard work. And so, possibly with trembling thumbs and a heavy heart, he typed the words that would restore balance to the universe—or at least improve his follower count.

Preceding his terse missive, he shared a shot of parts of the offensive article and dotted some words in red that, to him, begged to be asked “why”. Most strikingly, he positioned a red box on the left bottom corner of the page on which was written: “Why the need for such words, @straits_times?” in a ringing why you so lidat tone. The red box was no accident, but a visual cue loaded with symbolism. Mr Lim is a former graphic designer; he knows his dots and boxes. Red is the colour of correction, alarm, and emotional urgency. In school, all of us remember it as the ink of authority, used to flag mistakes. So when Mr Lim chose to set that phrase in red, he wasn’t just highlighting it; he was using it to disapprove. This is wrong, he could be saying. It’s fascinating, because instead of engaging with the critique intellectually, he responded emotionally—and visually. That red box is a digital sigh, a silent scream, a passive-aggressive post-it note to the world.

Somewhere between the third chamomile tea and the twelfth re-read of the ST article, he could have realised: the world simply didn’t understand his hard work

He was apparently upset by five words/phrases used. In the headline, he red-dotted “loving unknowns”. To someone curating a high-fashion gala, that phrase might sound like a backhanded compliment, as if the event lacked star power or polish and had to make do with lesser-known names. But here’s the kicker: “loving unknowns” is actually a beautiful concept. It suggests openness, curiosity, and a willingness to celebrate emerging talent. Many SOTD readers have not heard of Malaysian designer Dickson Mah until we wrote about his intriguing bra-top, shown at the ‘Next in Vogue’ gala. And happy they were, now that they know who he is.

Mr Lim was also displeased with ST for descriptive language. They wrote: “Fittingly for a title that has made a mission of foregrounding the tropics, there was a pasar (Malay for marketplace) feel to the ball.” He marked two words “pasar” and “marketplace”. It is possible that he felt the event was being framed as unsophisticated or lowbrow, despite its high-fashion intentions. But here’s the irony: pasar isn’t inherently pejorative. It’s a culturally rich term, evoking vibrancy, community, and grassroots energy. If anything, it could be seen as a compliment, an acknowledgment of accessibility or local or regional flair. Pasar, to us, was descriptive, not dismissive. It is also possible that he may have taken the word as a judgment of his taste or curatorial choices, rather than the event’s atmosphere.

Models of the evening’s fashion show, featuring the designs of Singaporean designer Putri Adif . Photo: voguesingapore/Instagram

It appeared that he was upset with the word “marketplace” too. Here’s the irony to the reaction. Fashion needs the marketplace. It isn’t just a backdrop, it’s the entire ecosystem. Without it, designers would be dressing mannequins in a vacuum. The marketplace is where ideas meet reality, where creativity becomes commerce, and where style finds its audience. ‘Next in Vogue’, a two-day event, is part of the marketplace. It isn’t a dirty word. From Paris’s marchés aux puces (flea markets) to Tokyo’s Harajuku, fashion has always thrived in spaces of exchange. To take offense at the word “marketplace” is to deny the very mechanism that gives fashion its cultural and economic power. It’s like a chef being offended by the word “kitchen”.

Then there is “yet to shed its start-up feel”. Mr Lim seemed unhappy that the magazine he worked so hard on for five years was so described. Some businesses are serial start-ups! In the case of Vogue SG, it could mean a refusal to calcify into legacy bloat. Rather than take it as a badge of creative energy, agility, and authenticity, he chose to absorb it as moral injury. The magazine is still operating with start-up energy—a tight team and experimental layouts—so the description is not off. For us, if having a “start-up feel” means we still believe in bold ideas, late-night edits, and the thrill of making something from scratch—then we’ll wear it like couture.

It appeared that he was upset with the word “marketplace” too. Here’s the irony to the reaction. Fashion needs the marketplace. It isn’t just a backdrop, it’s the entire ecosystem

The other word/phrase bindi-ed in red is one we can’t quite make out. It was placed between “but” and “not”, below “themselves” in the phrase, “themselves a crew of known but not quite famous creatives”. Was Mr Lim referring to this part of the sentence? Was he upset that the “known but not quite famous” was identified? What did he read into that? “We’ve heard of them, but we’re not impressed yet”? We did not think it’s a critique. It’s the truth. The fashion world is full of talented creatives who are known in niche circles, but have not crossed into mainstream fame. That’s not a flaw. It’s a stage in the journey. And frankly, it’s where some of the most exciting work happens. But, to Mr Lim, who was once also “known but not quite famous”, it probably smudged the illusion of prestige.

That dotted ST cutout was followed by the remarkably composed reaction to the unliked article, probably delivered through gritted teeth. Mr Lim started by saying that the gala celebrated storytelling, kinship, and paving the way for the region’s future creatives, proving it was about gratitude, not grandeur. The layers of self-mythologizing were almost operatic! Honestly, if the gala was truly about kinship and storytelling, then embracing diverse interpretations—including ones that use words like“ pasar” or “marketplace”—should be part of the story. But instead, we were supposed to be impressed with the image management masquerading as vulnerability.

Desmond Lim’s reaction on IG Stories to an ST story. Screen shot: monkiepoo/Instagram

And, finally, the true feelings emerged: “It is disheartening when moments rooted in care and generosity are reduced to cynicism.” We did not think that the ST article was cynical at all. There was no biting commentary, no sarcasm, no undercutting of the event’s intentions. It’s just not ST’s style. If anything, it leaned into the narrative that Mr Lim was trying to defend—one of care, generosity, and artistic ambition. And why “rooted¨? Why the farmer’s market ethos onto a champagne-soaked gala? His reaction appeared rather misaligned with the actual tone of the coverage. It’s almost as if he anticipated backlash and responded to a ghost of criticism that wasn’t really there. If something is indeed “rooted in care and generosity”, surely it can take scrutiny.

After many years attending fashion events, we have learned that the uninspired wearing virtue’s disguise is a frequent occurrence and a timeless spectacle. It is emotional deflection sequinned as moral high ground. The desire to underscore the care and generosity as the heart of the event is understandable. It is, however, also true that more care could’ve gone into the execution of the event. Reducing criticism to cynicism is a convenient way to dodge accountability, especially when the audience simply called it like they saw it. Desmond Lim’s response appeared to be deployed when the spectacle itself is shaky, and the emotional scaffolding—generosity, care, intention—is all that’s left to defend it. Perhaps, true generosity accepts that not every moment deserves a standing ovation.