After leaving British Vogue, Edward Enninful is still in the magazine business. He has launched a new title, 72, his very own It-number-as-mag

Edward Enninful, the much lauded, former editor-in-chief of British Vogue, has launched a new magazine with a somewhat cryptic number as its masthead: 72. In the Ming dynasty (明朝) Chinese classic Journey to the West (西游记, xiyouji), the central character, Sun Wukong (孙悟空) is known for his extraordinary magical power of 72 Transformations (七十二地煞变化, qishier disha bianhua) or, specifically, ‘earthly-fiend’ transformations. The specific quick-changes are not mentioned in the book, but we do know two other characters have similar power, the God Erlang (二郎神, erlangshen) and the Bull Demon King (牛魔王, niumowang). But the number 72 is also mentioned elsewhere in the novel, including the 72 caves on Mount Huaguo (花果山, huaguoshan) or Flower-Fruit Mountain and the 72 celestial generals sent by the celestial court to subdue the Monkey King when he created chaos in heaven. Nothing so grand for Mr Enninful’s magazine: 72 is the year of his birth.

This prosaic fact—that the magazine’s title marks its founder’s birth year—aroused our curiosity about the business itself. At a reported price of £18 per issue (or about S$31), double the price for British Vogue, we wonder if the reader—assuming that there are many of them—paying for a myth, or a magazine. This seemingly simple transaction is, we contend, a finely styled stratagem in a much larger corporate game. The magazine, a quarterly print publication and a digital platform, was launched yesterday in London under Mr Enninful’s fresh new venture, a “media and entertainment company¨, EE72. In a pre-launch publicity blitz, the stylist-turned-editor told BBC: “While people say print is dead, I believe the opposite—print has become more powerful than ever and an art form that must be preserved.” He did not say how or why print has gained new gravity, and the answer, we suspect, is not in the art, but in the arbitrage.

“While people say print is dead, I believe the opposite—print has become more powerful than ever and an art form that must be preserved.”

Edward Enninful

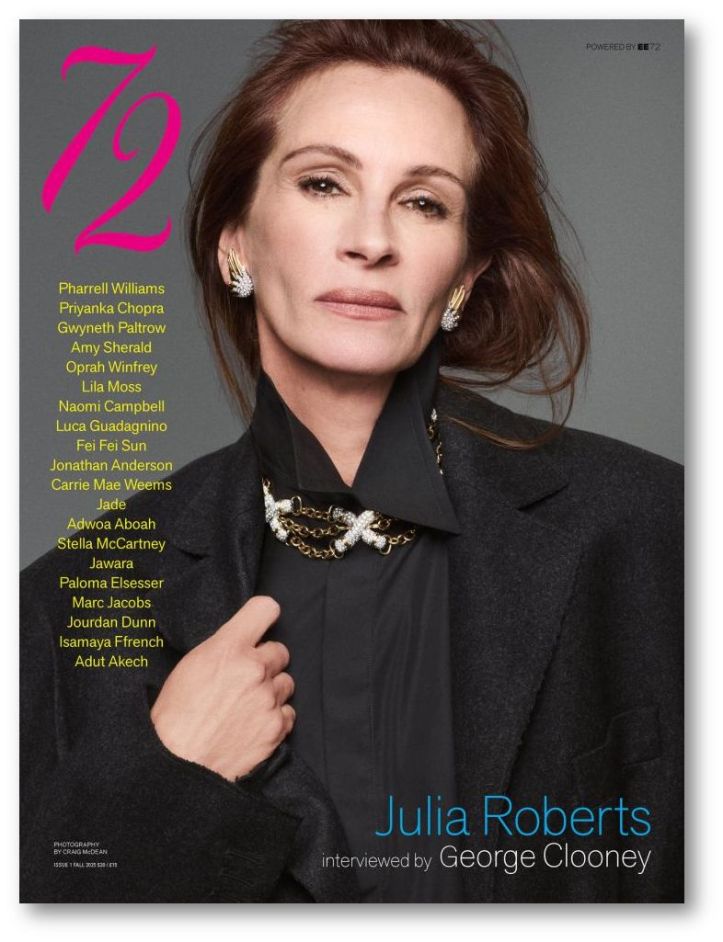

His new baby is a mix of fashion and celebrity news, heavily driven by the latter. Mr Enninful is known to be friendly with many stars and celebrities anyone cares to know more about. And he let it show. Unlike the typical magazine of its ilk, 72 has made do without cover blurbs. Instead, it offered a list of 20 celebrity names (we’re surprised it’s not in alphabetical order or tick-boxed!) and the celebrity cover model and her interviewer, also a celebrity: “Julia Roberts interviewed by George Clooney”. By now you would have read the reactions to Ms Robert expression on that inaugural cover. And they are they are not wring. Photographed in London by Craig McDean, featuring the actress in Phoebe Philo, it looked less a specifically commissioned cover shot that an image taken from a fashion feature, either ‘A Matron’s Day Out’ or ‘How to Dress for Funerals Today’.

Although it has an unusual name for a lifestyle title, 72, is not the first magazine to sport numbers as their masthead. In the UK, there is 10, a bi-annual British fashion magazine named after the number associated with the perfect or the top-tier, while in Germany there is 032c, a title chosen to refer to a colour code in the Pantone Matching System. Closer to us is Japan’s long-running 25 Ans, named after the French phrase, ‘25 years old’. It continues to be popular today. The choice of a two-digit numeral is, however, still uncommon in the fashion magazine sphere. But Mr Enninful’s seemingly cryptic number isn’t what it denotes immediately, but what the brand makes it mean over time. Vogue is a word with inherent meaning, even if a tad old-fashioned, but a number like 72 must earn its cachet through its covers, its articles, and its overall aesthetic.

Julia Roberts with Edward Enninful during the shoot for 72. Screen shot: ee72/Instagram

In a world made smaller by pervasive online “content creation”, where every title is vying for attention, the cryptic number dares to be different. But, the celebrity editor-driven title is a well-documented risk. We remember Mirabella (1989—2000), the for-over-40 magazine founded by the ousted-from American Vogue editor Grace Mirabella. It started with a good editorial vision, but it struggled with its identity over time. Then there is George (1995—2001) founded by John F. Kennedy Jr. to bridge the gap between pop culture and politics. It had a unique premise, but its fate was inextricably linked to its founder. When JFK Jr. tragically died in 1999, the magazine lost its heart, its celebrity face, and its primary source of public relations. Most current is CR Fashion Book, the title of another former Vogue EIC, Carine Roitfeld. The high-fashion quarterly largely followed a traditional business and product model. While it has not folded, it has struggled to maintain its initial buzz and commercial viability.

Mr Enninful told The Guardian that the 72 format and high-end production are designed to be “tactile, timeless and collectible”. This likely targets a niche audience that values in-depth reporting and high-quality print over disposable content, such as the popular ‘listicles’ (The Ten Best Lipsticks to Buy Now or, for something more current, “Giorgio Armani’s 9 Most Iconic Red-Carpet Looks Of All Time” ). It seems Mr Enninful wishes to treat 72 as an art object to be adored, rather than merely a monthly product with commerical overtones. But, that, too, is not exactly untried. Editor-founded magazines-as-art-objects, such as Visionaire and the poster-size Manipulator, have faced significant challenges and, in some cases, have ceased publication.

The pages of 72. Photo: 72

Visionaire, founded in 1991, was the archetype of the ‘art object’ magazine. Each issue was a limited-edition, conceptual-art piece that defied the standard magazine format, featuring everything from scented pages to a seven-foot-tall issue to one featuring a complete paper pattern from Comme des Garçons. However, its business model was both its genius and its eventual downfall. The cost and complexity of manufacturing each issue were immense, making it difficult to sustain commercially. It was more of an art project than a scalable business. Similarly, Manipulator (1984-1994) was loved for its massive, poster-sized format that did not allowed casual reading in Starbucks. The magazine was so large that fans had to carry them, rolled up in a tubular cardboard poster housing. The content prioritised art and photography over a traditional publishing model. It closed after a decade, with its founders stating they chose to “end it while the magazine was still cherished and esteemed”, rather than let it decline.

In a corporate world that often seems to expect unwavering loyalty, we find a curious paradox in the figure of Mr Enninful, who is still on Condé Nast’s payroll, even 18 months after he announced his leaving British Vogue. At the time, suspicions were rife that Anna Wintour was not pleased by the chatter that he may move to the U.S. to take over the American edition of the magazine. Even without a Vogue under his belt, Mr Enninful did not, however, strip himself off the soft armour of a corporate titan. He accepted the role of “a global creative and cultural advisor” for Vogue that the media described as a “promotion”. What that climb-up entails has not been publicly clear. While he has stated that his new venture is for “the next generation”, the arrangement is not without a whiff of mystery since it does not involve Teen Vogue. If he is so eager to re-thread his career, why does he remain bar-tagged to the very corporation he is seemingly challenging?

In a corporate world that often seems to expect unwavering loyalty, we find a curious paradox in the figure of Mr Enninful, who is still on Condé Nast’s payroll

This somewhat baffling tether is, as we see it, no mere coincidence, but a tactical corporate stratagem—a set of ‘golden handcuffs’, as some in the industry have suppose—designed to serve the very interests of the corporation he has set out to compete with. Mr Enninful is an influential figure, who counts the likes of Naomi Campbell as a personal friend (naturally, she appears in 72). It could be advantageous for Condé Nast to retain him in some capacity. His position in the organisation wonderfully allowed him to pursue his own interest. Keeping Mr Enninful on the payroll in a highly compensated deal, even if vaguely defined, allows Condé Nast to ensure that a key rival cannot hire him. Keep a tight orbit around your most valuable star. It could also provide the option of buying EE72, should the occasion arises.

We worry for Mr Enninful. The media these days is measured by clicks and reach, and 72 enters the fray as a high-minded publication, seemingly yoked to a corporate compromise and a business model, that’s more of a cautionary tale than a prospectus. Its grand ambition to be a collectible art object or a beacon of taste seems at odds with a first issue that feels less like a new dawn, and more like an elevated version of the magazine it seeks to supplant. In this battle for cultural authority and editorial supremacy, Edward Enninful is not just competing with Vogue’s storied legacy; he is gambling that his personal brand and vaguely defined product can triumph where so many others have failed. It left us wondering, as we eyeballed Julia Roberts’s look of unadulterated glee, if 72 will outlast its predecessors. Or, if its first issue will be remembered less for its art and more for the quiet artifice of its existence.

Photos: 72/EE72