The Italian maestro of soft tailoring has died, age 91. He left behind an empire that is more than just the elegant clothes he designed

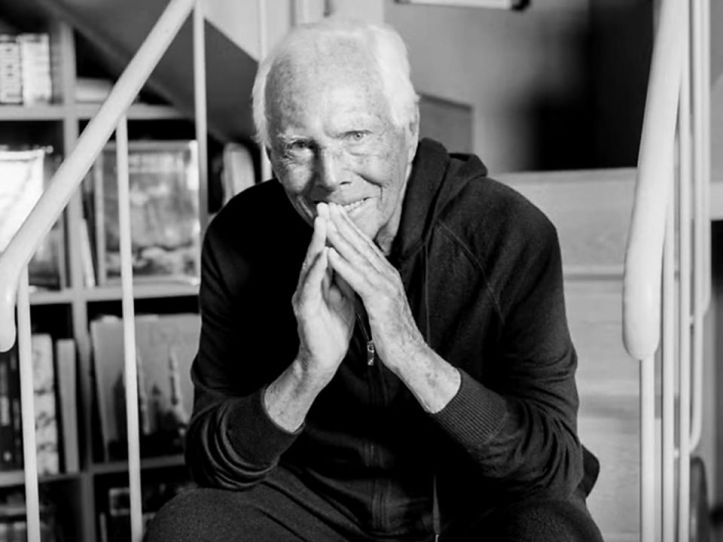

Giorgio Armani, remained silent about his successor to his death. Photo: Olivier Kervern/Elle

It is news that keeps appearing on our push notification. Every media outlet has covered it, everyone interested in fashion is talking about it. “The king”, they call him, has passed away. Giorgio Armani, probably the most recognised name in fashion today, died on Thursday (Italian time), according to a statement put out by the Armani Group at about 9.30pm (our time). It did not specify a precise cause of death, stating somewhat uninformatively that Mr Armani passed away “peacefully, surrounded by his loved ones”.

However, various news reports have since indicated that he died due to “complications linked to age-related illness”. His declining health had been noted publicly when he missed several key events, including a fashion show in June, which was a first for him in his decades-long career. Reportedly, he had been recovering from an undisclosed condition and a lung infection. The general consensus from the reports is that his death was a result of his advanced age and related health issues.

Mr Armani’s last public appearance at the Armani Privé spring/summer 2025 show in January this year. Screen shot: armani/Facebook

R.I.P messages, as well as tributes have flooded social media. Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni, posting on X, called him “an icon, a tireless worker, a symbol of the best of Italy”. Cate Blanchett, a brand ambassador and customer posted an Instagram a reel of her kissing Mr Armani’s hand backstage at a fashion show with the comment, “Giorgio Armani, you will always be remembered.” Chinese model Hao Yunxiang (郝允祥), who has been on the Armani runway for the past ten years, shared on IG in English: “The interaction in work will be a lifelong treasure of mine. The Armani spirit lives on forever.” Commenting on the statement the Armani Group shared on IG, Donatella Versace wrote: “The world lost a giant today. He made history and will be remembered forever.” Her remark was significant, considering the known rivalry between the two brands, often summarised by the phrase, attributed to Anna Wintour, that “Armani dresses the wife, Versace dresses the mistress.”

Giorgio Armani will be remembered not only as the giant he was, who defined modern power dressing, but also in the complete, minimalist world of ethereal elegance he meticulously built and offered as a way of life. Many equate the Mr Armani with clothes, but his vision wasn’t a static concept; it was a living, expanding universe he built over decades. He didn’t just sell products either, but incrementally, year after year, built a complete and cohesive world that his customers really bought into. He showed rigorously how to live in style.

Mr Armani with one of his favourite Chinese models Hao Yunxiang. Photo: haoyunxiang/Instagram

He understood early on that a brand’s presence could extend beyond clothing. By the early 1980s, he signed an important licensing agreement with L’Oréal to create Armani Beauty, which included perfumes and cosmetics. This was a crucial first step, as fragrance and beauty are often the most accessible entry points to a luxury brand. Armani cosmetics are known for their focus on haute couture makeup, offering luxurious products with avant-garde formulas and a signature “Armani glow”. In later years, the cosmetic line was so extensive that it was dubbed “wardrobe for the face”.

Next came the first lifestyle extension. In 1998, he created Emporio Armani Caffè in Paris, way before the current tend of brand eateries that deliver less than do with clothes. (In the mid-2000s, the cafe became Armani/Caffè.) Four years after the first Caffè, the world of gourmet confections was introduced—Armani/Dolci. Even a small box of chocolates was an opportunity to showcase the signature Armani aesthetic through its minimalist packaging and high-quality ingredients. In Japan, Armani/Dolce chocolates are the most coveted as gifts for Valentine’s Day.

Armani/Fiori in Hong Kong. Photo: Armani

In 2000, Armani launched Armani/Casa, a home interiors collection. The line included everything from furniture and textiles to lighting and decorative objects, proving that his aesthetic was not limited to what people wore but extended to the very spaces they lived in. Homes, Mr Armani felt, needs to have flowers, so he introduced Armani/Fiori, a floral design service and boutique. Much like his other ventures, this wasn’t about simply selling flowers, but about arranging them with his signature architectural precision and clean, minimalist style. It was a subtle yet powerful extension of his aesthetic into another element of daily life.

The ultimate expression came in 2005 when he launched Armani Hotels & Resorts in a partnership with Emaar Properties, the Dubai-based real estate development company known for the Burj Khalifa and The Dubai Mall. The first Hotel Armani opened in 2010 inside the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, and a second followed in Milan. These hotel projects were the culmination of his vision—he personally oversaw every detail, from the minimalist furniture to the lighting, to create a physical space that was a complete immersion in the Armani aesthetic. Or as some travellers have said, “strictly for fans only.”

Armani/Caffé in Hong Kong. Photo: Armani

Mr Armani was also a fiercely independent architect of a complete lifestyle who proved that timeless vision could triumph over corporate consolidation. From the 1990s onward, his brand was a constant target for acquisition, but he resisted every overture. His reasoning was consistent and deeply personal: joining a large group would inevitably lead to a dilution of his core values. His independence gave him a level of control that is almost unheard of in the modern fashion industry. As the sole owner, CEO, and creative director, he could greenlight any project, from a new hotel in Dubai to a line of chocolates, allowing him to maintain a singular, unwavering vision across all his ventures.

Even in his last days, his commitment to independence was his final act of defiance. The weekend before his death, the Financial Times published what the paper touted as his last media interview, in which he said, “My greatest weakness is that I am in control of everything.” Mr Armani also reiterated his long-held belief that his succession should be “organic” and not a sudden “moment of rupture”. He named his key collaborators and family members as part of a gradual transition process, ensuring the continuity of his company’s independent spirit and creative vision. Till the very end, Giorgio Armani undoubtedly believed true power was not in ownership, but in control.