Before it makes its way to the market, one Adidas sandal, conceived with Willy Chavarria New York is accused of slightly stolen valor

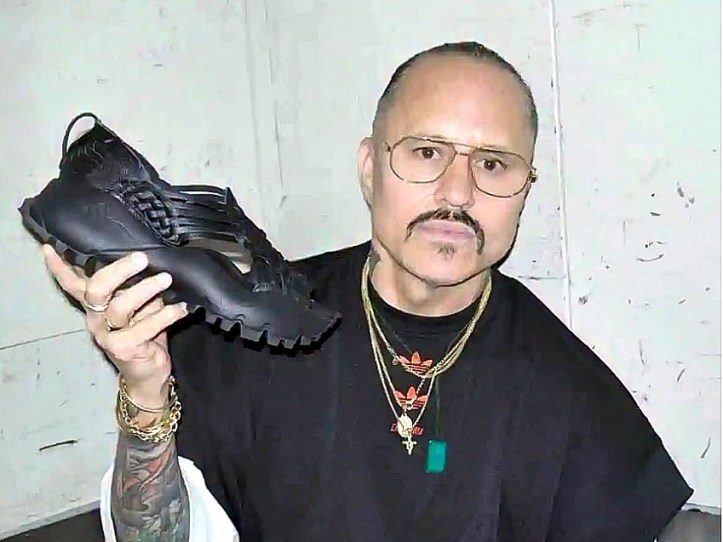

The Willy Chavarria X Adidas Originals ‘Oaxaca Slip-On’. Photo: willychavarrianewyork/Instagram

First, it was Prada. Now, it’s Adidas. Just this past June, the Italian brand was called out for showing slippers on its runway that bore an uncanny resemblance to India’s recognisable Kolhapuri chappals. Two months later, the German brand is accused of creating a new shoe design with the American designer Willy Chavarria that is inspired by the traditional huarache sandals made by Indigenous communities in the southeastern Mexican state of Oaxaca, famous for their expressive handicrafts. The Adidas Originals-branded sandals, described as “fine athletic footwear”, are named ‘Oaxaca Slip-Ons’—a moniker that does not lead on to whether it refers to the product or the Mexican region. It could be chosen to obscure the sandal’s design provenance. While the visual similarities have dominated the headlines, the real story delves far deeper. It is not just about copying; it is about the erasure of context and the appropriation of a design for commercial gain.

Adidas stands accused of using the “collective intellectual property” of an Indigenous community without their consent, a meaningful partnership, or, most critically, compensation. Many of the brand’s customers, the name Oaxaca would be an exotic-sounding label, not a region of Mexico rich in culture and heritage. The lack of identifying the origin of the design is exacerbated by where the shoes are manufactured—not in Mexico, but in China. The use of the name Oaxaca without direct collaboration with the community is seen straightaway as a form of cultural and economic exploitation. It is not that there is no sizeable footwear manufacturers in Mexico to support what is expected to be a limited-edition issue; it is that Adidas wilfully ignored the Mexicans altogether. For some, closer scrutiny revealed that Adidas’s version bore a resemblance to the huarache from the state of Michoacán than Oaxaca. Naming the shoe after the latter shows more: the lack of understanding of cultural nuances.

Traditional huaraches in a Mexican market. Photo: AP

Adidas and Mr Chavarria are not merely aping generally inexpensive sandals from Mexico. That the collaboration has been dubbed as “Fine Athletic Footwear” indicate that brand and designer have planned to sell their elevated version—quite literally since they come with chunky soles—as expensive versions, which further exacerbates the charge that no economic benefit was considered for the Mexicans, who continue to make the huarache for a living. This isn’t a case of inspiration, like Nike’s Air Huarache, which has a fundamentally different aesthetic form; the Adidas design is unambiguous in its origin. The brand’s premium iteration is, therefore, a stark contrast to the often modest pricing of traditional huaraches, not worn as luxury footwear. By re-branding and selling a similar design at a significantly higher price point, the collaboration can be—and is—seen as devaluing the original craft while profiting from its design.

It is not as if a model for respectful, creative, and profitable collaboration does not already exist. A number of brands (including smaller ones) have proven that ‘inspiration’ can lead to genuine partnership. Nike, for instance, has a long-running N7 initiative, which has moved from symbolic support of Native American communities to directly co-creating collections with Indigenous designers like Tazbah Chavez and Elias Not Afraid and athletes such as softball star SilentRain Espinoza. The Mexican designer Carla Fernández has also built an entire brand on a model that preserves and revitalizes the textile legacy of Indigenous communities, ensuring that artisans are fairly compensated and their techniques are protected. In Asia, the Japanese are known to continue to support their master craftspeople. A name that immediately comes to mind is the late Issey Miyake, who in 1998 collaborated with bamboo master Kosuge Shochikudo to co-create the stunning bamboo bodices and hats that featured in the spring/summer collection of that year. In the face of such clear examples, Adidas’s decision to bypass partnership seems all the more cynical and inexcusable.

Willy Chavarria holding up a side of the Oaxaca Slip-On. Photo: willychavarrianewyork/Instagram

Even Prada, shod in their own recent scandal, set a precedent by dispatching a team to India to meet with artisans, paving the way for a made-in-India collaboration. This move signaled a serious intent to understand the craft and engage with the community. In contrast, Adidas’s response has been more reactive and less collaborative. While Mr Chavarria, who is no stranger to using ‘found object’ for inspiration, has apologised, even issuing a statement to AFP to say that he “deeply regrets that this design has appropriated the name and was not developed in direct and meaningful partnership with the Oaxacan community”, Adidas has not released a detailed, public statement. Their position has been conveyed through a reported letter sent to Oaxacan officials and confirmed by Mexican government representatives. Adidas states that they “deeply values the cultural wealth of Mexico’s Indigenous people and recognizes the relevance” of the criticisms being made and desires to discuss how it can “repair the damage” to the Indigenous populations. The company has not offered a specific form of compensation, but it appears open to negotiating some form of restitution.

Still, it is not clear where Adidas truly stands on the issue. The brand’s decision to engage in private, high-level talks with government officials, rather than with the affected artisans themselves, is, at best, archaic. The problem is being treated as a legal and political dispute to be settled with a suggestion of restitution, not as a cultural harm to be repaired with respect and collaboration. Profits over people? In a world where consumers, armed with social media, are demanding a more human and ethical approach to fashion creation, the Adidas reaction contrasts as starkly as open-toe sandals and patent pumps. Corporate responsibility must not only kick in after poor design decisions are called out. However “fine” the Adidas footwear is, that marketing language is just an act of strategic commerical elevation. It is, ultimately, a hollow promise. Words, as any marketer with a flair for puffery knows, can be used to obscure deplorable brand actions. True intentions are shown in what we do, not what we say.