After a firestorm over American Eagle’s commercial, Dunkin’ has now entered the fray with a similar reference to ‘genes’, proving again that the ghost of eugenics and its exclusionary language remains a potent force in American advertising

Gavin Casalegno in a Dunkin’ Donut commerical. Screen shot: dunkin’/YouTube

It did not end with American Eagle (AE). From “blue” to “golden”, the jeans/genes reference is riding the crest of a wave of controversy. The latest brand to find itself at the center of a social media firestorm is Dunkin’ (of the Donut fame). This is arousing criticisms that brands stateside appear to be attempting to capitalise on several broader societal currents. The brand’s commercial in question features the model-turned-actor Gavin Casalegno (of The Summer I Turn Pretty fame), dressed in a lightweight white shirt and striped board shorts, hawking an iced drink. Seated by a pool, he said: “Look, I didn’t ask to be the king of summer. It just kind of happened.” He stands up and swaggers towards the camera. “This tan? Genetics. I just got my colour analysis back. Guess what? Golden summer. Literally.”

The word is no longer hiding behind a double entendre, as it was in American Eagle’s campaign with Sydney Sweeney. For many, ‘genetics’ is unpalatable due to its historical ties to the controversial eugenics movement. Using it in a positive light could be considered a coded nod to white supremacists and other extremist ideologies that have adopted eugenics-related rhetoric. In addition, the word choice is believed to reinforce narrow beauty standards: mainly white and fair-haired, such as Ms Sweeney and Mr Casalegno. This has been interpreted as a not-so-subtle message that certain physical traits are inherently superior, which is a core tenet of eugenics. While advertisers might intend to use “genetics” as a synonym for natural or to imply “high quality”, the term is now inextricably linked to a history of discrimination and harm.

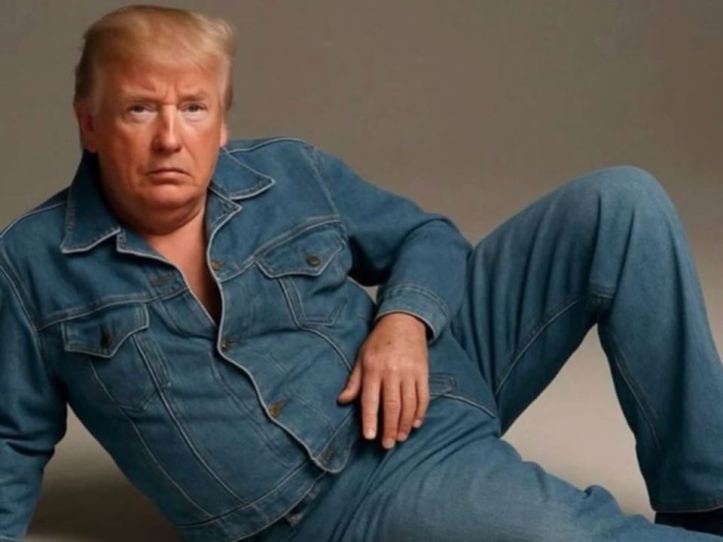

Pretend Sydney Sweeney. Photo: donaldjtrumpjr/Instagram

The Dunkin’ advertisement came not only hot on the heels of the American Eagle controversy, but the Trump family reactions to the latter. Shortly after the AE criticism went viral, Donald Trump Jr shared on Instagram an AI-generated image that showed his father lying on the ground in the same pose and wearing similar double-denim outfit as Ms Sweeney. It included a now-deleted comment: “That Hanse…. Um, Donald is so hot right now!!!”, referencing a line from the 2006 fashion satire Zoolander. The post was clearly a political jab, mocking what he viewed as essentially a “woke” uproar. To his fans, it was a hilarious troll. To his critics, it was tone deaf and down-right bizarre. To add another layer to the debate, Donald Trump reacted to it on his Truth Social: “Sydney Sweeney, a registered Republican, has the HOTTEST ad out there. Go get ’em Sydney.”

You’d think that the AE fiasco would not score political capital. But the Trumps’ reactions were a key turning point, moving the discussion from a marketing debate into a full-blown political culture war. By identifying Ms Sweeney as a “registered Republican”, the president has additionally made the situation about political identity and, no doubt, loyalty. The actress was inadvertently drafted into the ongoing political battle; she can now be seen as a MAGA celebrity, a conservative icon, no matter if she desires the labels or not. The Trumps have yet to comment on the Dunkin’ commercial, but people are wondering why a coffee-and-donut company would reference genetics in an ad for just another drink in the crowd beverage market. The timing, combined with the focus on Mr Casalegno’s “tan” and “golden” colouring (Mr Trump’s fave. Fortunately, the copywriter was careful not use orange), was seen as another example of a brand playing with racially charged themes, not unlike Mr Trump’s rhetorics.

Drink in hand, Mr Casalegno touted his “tan” and “golden” colouring. Screen shot; dunkin’/YouTube

The words in question that both Sydney Sweeney and Gavin Casalegno were made to utter sounded like they were chosen to celebrate specific physical traits in a way that felt exclusionary. Dissenters of the negative reactions to the advertisements call them “woke outrage”. But it is reductive to come to such a dismissal. The direct and logical response is unsurprising, especially when a brand deploys a prepossessing celebrity to attribute a positive physical trait (e.g. being beautiful, fit, or having a great tan) to their “genes” or “genetics”. It sends a very specific message: that a person’s value is a result of a random biological lottery. The criticism is, therefore, not “woke” in the pejorative sense. It is a legitimate call out to brands that are flippant in their word choice.

The most potent part of the debate isn’t about the word “genes” or “genetics” in a vacuum; it is about the words being used to celebrate specific physical traits—the very pulchritude that allows the bearers to peddle products, and be handsomely paid. This is where the historical connection to eugenics becomes hard to ignore. The public’s increased awareness of the issue, combined with the context of modern social and political concerns, has made the use of “genes” in advertising a sensitive and, as it is presently seen, offensive choice. In a highly polarised cultural climate, consumers are scrutinising every message from brands and those politicians keen to amplify and weaponise the marketing blunder into a culture conflict. For some, controversy is no longer a political risk; instead, it is a tool for personal branding and, regrettably, a symbol of ideological loyalty.