First he told kids they needed less dolls, now he is threatening doll maker Mattel with 100 percent tariffs, as if the company were a country. Was Donald Trump traumatised by the likes of Annabelle when he was a child?

Mattel’s Barbies remain important among dolls, old and new, at all toy stores

Donald Trump must loathe dolls. His aversion to them is so intense that he wishes those who desire Barbies, for example, to have less. To illustrate his point that even children have to suffer because of his tariff policies, he did not choose Lego bricks, Transformer bots, or Hot Wheels. Rather, he picked dolls. At a cabinet meeting on the last day of April, he said: “Maybe the children will have two dolls instead of 30 dolls.” In an interview on NBC’s ‘Meet the Press” days after, Kristen Welker asked Mr Trump if his tariffs “would cause some prices to go up” or “supply shortage”, such as those of dolls. He replied, “I’m just saying that they don’t have to have 30 dolls. They can have three; they don’t need to have 250 pencils, they can have 5.” He later added, “I’m basically saying we don’t have to waste money on a trade deficit with China for things we don’t need, for junk we don’t need.”

One man’s junk is another child’s treasure. Mr Trump has overlooked the subjective value and importance that toys hold for children. What might seem like a superfluous item to an adult can be a source of immense joy, creativity, and learning for a child, even comfort. Mr Trump very likely has not heard of Labubu. His doll rationing proposal is ironic as it totally overlooks the Labubu phenomenon. He suggested children should have fewer dolls when adults themselves are fervently embracing them. The Labubu craze is a significant economic driver in the toy and collectible market, with blind boxes and rare figures—a largely Asian merchandising idea—fetching high prices. This directly contradicts his belief that these dolls are mere “junk”. Mr Trump showed once again how out of touch he is with current consumer trends, as well as with the diverse ways in which people engage with dolls.

Barbie and furniture for her doll house

When Republican senator from Wyoming Ben Barrasso was recently asked by Ms Welker what his thoughts were regarding Mr Trump’s telling parents to place a quota on what their kids can have, he said: “The president, I think, is very effective at using the bully pulpit.” The term “bully pulpit” was coined by President Theodore Roosevelt, who considered the presidency as a platform to advocate for his agenda. But the “bully” part of that phrase is, to us, problematic: By singling out a seemingly unrelated but attention-grabbing issue about children’s toys in the tariff discussion, Mr Trump effectively controlled the narrative and steered the aggressive framing towards his narrow point of view: “Don’t worry about higher prices; just buy less.” Clearly, that is a bullish way of dismissing valid concerns.

Another irony: Mr Trump is known not to have had a hand in raising any of his children, yet he saw it fit to part unsolicited parenting advice. In a 2005 interview with shock-jock Howard Stern, the then-businessman gleefully said that he “won’t do anything to take care of” his children. “I’ll supply (the) funds and she’ll (second wife Marla Maples at the time) take care of the kids.” It’s certainly plausible that he has had very little, if any, direct involvement in the raising of his kids, including the purchasing of dolls for any of them (has he ever held one?). Trump’s lack of real parental experience do not position him as an expert on child development or the needs of kids. His pronouncements on how many dolls (and pencils) children should have, therefore, lacked credibility, if not insight.

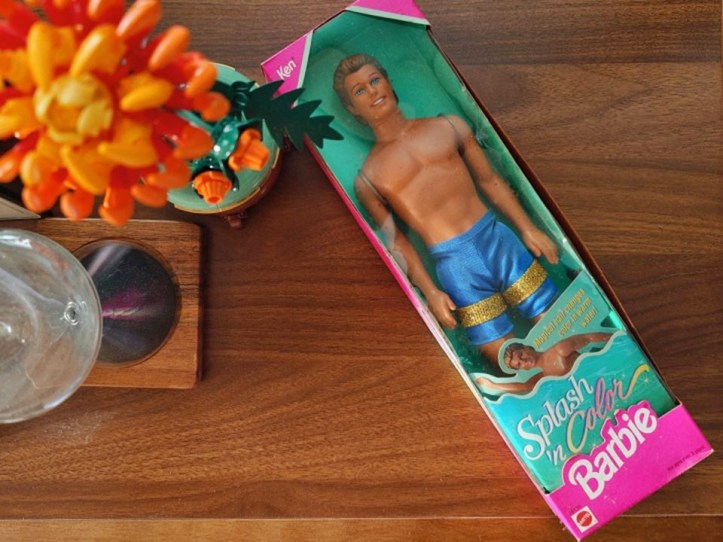

Vintage Ken doll from the ’90s

But telling parents to buy less dolls for their kids was not enough. Last week, Mr Trump threatened one of the world’s biggest doll makers Mattel with tariffs, as if the company was a country. Mattel CEO Ynon Kreiz told CNBC that the company would have to raise prices as their products are made in China. In response to that business decision, Mr Trump told the media at a press gathering: “We’ll put a 100 percent tariff on his toys, and he won’t sell one toy in the United States.” It is a very strange warning. The U.S. economy is heavily reliant on consumer spending, which makes desiring a major retail company not able to sell one product a problematic economic message. Toys may not be essentials, but American spending on non-essential goods is a significant driver of retail sales. Telling businesses to sell less and consumers to buy less could have negative consequences for retail businesses and the broader economy, which relies on this consumption to drive growth.

Donald Trump’s berating of Mattel crescendoed into something even more belligerent. On Truth Social last Saturday, he told Walmart, also a seller of Mattel products, to “Eat the tariffs” when the nation’s and the world’s largest retailer warned that prices would increase due to Mr Trump’s import taxes. More “bully pulpit” talk? By using an aggressive tone to tell Walmart to absorb the costs, he attempted to downplay the potential negative impact of tariffs on consumers, which is a strange way of trying to convince the public that his trade policies won’t lead to price increases. It is confusing—and counterproductive—to simultaneously tell Walmart to absorb tariff costs to prevent price increases, and tell parents to buy fewer things, such as dolls. It is not clear why Mr Trump chose dolls to discourage spending. It is possible that he’s projecting his own lack of connection with dolls onto others, assuming that their experiences should mirror his. Or could it be that he has a fear of them—Anabelle, Chucky, or Brahms (from 2016’s The Boy), and the rest of the cinematic gang?

Photos: Chin Boh Kay