In the wake of resigning from FashionValet, the online business she and her husband started amid the scandals that have plagued the company, many are now asking, who is Vivy Yusof, really?

She’s the face on the radio/She’s the body on the mornin’ show/And she’s there shaking it out on the scene/And she’s the color of a magazine

—She’s in Fashion, Suede

Eighteen-minute read

From the beginning, it was about the duck; not the drake, but the duck. And the duck was a proud one, not an ugly duck(ling). Vivy Yusof’s blog page Proudduck.com, now defunct, was musings-turned-métier. Whether pride—or birdie self-esteem—fueled her success is hard to say. But Ms Yusof, the enviable “mom-preneur” to her fans and “mom author” to herself, is not afraid to be proud. A year before turning thirty in 2016, Forbes eagerly called her “the perfect poster child of the modern, Malaysian woman.” It was pride she could embrace. When she joined the club of the big three-O, the publication was even more complimentary: She became “Malaysia’s youngest e-commerce mogul” for the success of her FashionValet platform. It is hard not to imagine that such accolades bestowed on one individual so effusively would not go to the head. Until the recent controversy regarding her company and two of Malaysia’s government-linked organisations that required her and her husband to issue an apology/explanation on Instagram, Ms Yusof is the mouthpiece of FashionValet and its attendant businesses that won’t be hushed.

It helps that Ms Yusof is not unattractive. The camera loves her and she loves it back. Part of her appeal, apart from her less common trajectory as a Malay woman, is how she looks: glowingly fair, with large, speaking eyes, and incandescent smile, all set in a face that is immaculately proportioned, framed by sleekly-styled tudung—loosely, Malaysia’s answer to the hijab—which, as in the Middle-East, is an important part of the Islamic dress code for Muslim women. Or what Ms Yusof called “a wholesome 360-degree representation of a Muslim’s lifestyle”. It is also this comeliness that fronts her business. FashionValet Group adopts no spokesperson, such as Michelle Yeoh (whom Ms Yusof admires) for Balenciaga. The co-founder of FashionValet is the self-appointed ambassador of her own business, often described as an enterprise, built through her “personal branding”. As she has said, “the only person who knows the brand better is me.” Whether that is reputational heft or a way to cut-back on marketing cost is not immediately certain.

Going corporate, Ms Yusof proudly showing off office wear from her own The Duck Group label. Photo: vivyyosuf/Instagram

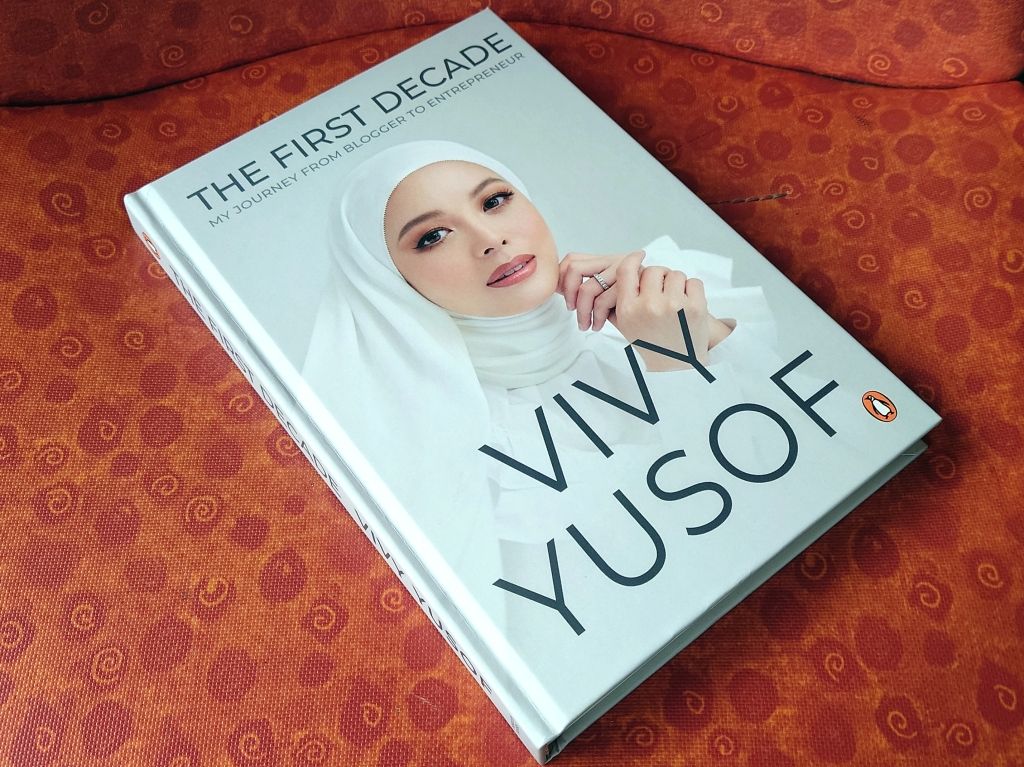

Although she frequently calls herself an “entrepreneur (her fans and the media like to precede that with ‘celebrity’, which she claimed not to like—in fact, she “hates” it—or understand)”, Ms Yusof seems to enjoy writing too, possibly over and above managing the business that is now in its 15th year. In fact, it can be sensed that she is more interested in being a media personality than a business owner, frequently accepting editorial interviews and inevitably talking about her authorship. (There was even a post on IG last August that “a podcast is coming and you’d want to watch it”.) Apart from her blog (we are unable to re-read any entry now since it is closed), there is the memoir, The First Decade: My Journey from Blogger to Entrepreneur, that was published in 2022 to enthusiastic reception. According to her, it made the best-seller lists across the region. In the book, she wrote that before she created Proudduck, she “really wanted a writer’s job at Vogue”. She ended in the pages of the New Straits Times in 2018. The stint as a “columnist” yielded, as it appears, only two articles, both about pregnancy and motherhood.

She writes not quite the stuff destined for a Pulitzer Prize nomination. Her narratives, always in the first person, are girlfriend-to-girlfriend conversational, and probably pitched to be relatable to her horde of fans, some of whom refer to her as “queen”. They are also “the community that basically raised me”, she said in a 2023 podcast on Billion Dollar Moves. The blog posts drew followers who stayed with her because, at the time, she was one of the few Muslim women writing about her above-average life (and “randomest things”) from a place few dared dream to go—London. It is in the British capital where she met the “love of my life” (who, at first, found her “bimbotic because I was carrying a designer bag”), where she went to university (London School of Economics) and graduated in law, where she wore “tube dresses” she was afraid her family would see, where she started the blog (encouraged by a friend) that led to the birth of FashionValet, and a subsequent writing career that has been, by most accounts, successful.

The now-defunct blog page Proudduck. Photo: vivyyosuf/Instagram

Her writing—including a stint as guest editor (and as cover girl) for the debut issue of Glam Hijab magazine, sister publication of the 21-year-old, high-society title Glam—culminated in the 2022 autobiographical self-promotion, The Last Decade. Vivi Yusof truly believes she was born to write. She has constantly regaled interviewers with stories of her love of writing, even from an early age, when she combined entrepreneurial fervour (a recurrent theme) with writing shine. In Standard Three or when she was nine, “I started writing a book,” she wrote. Self-published, no less. “I was so influenced by Sweet Valley Kids that I started writing stories of my own.” Fashioned after the spin-off of the America book series Sweet Valley High (mostly by ghost writers) and penned in an exercise book, it was then rented to her schoolmates to read and, when she found an illustrator to contribute to the book, increased the rental price.

In her memoir, she said, that Proudduck was started by a friend to get her into blogging. But she did not really explain why the name was chosen. In interviews with the media, she said the moniker referred to what she and her friends called themselves in school (whether it was at LSE or even before, she did not elaborate, although there is apparently a post dedicated to the naming). Why they identified with a fowl is not certain either or if she had used the Malay equivalent, itek back then. It is also unknown if she was aware that in Chinese, 鸭 (ya or duck) has a lot less noble connotation. But, Proudduck was drawing views—“a few thousand”, she said on Billion Dollar Moves. It reached even Brunei, where one fifteen year old started her blog Pusha’s Memories in 2016 because Proudduck “hit so bad”, she was unable to stop reading it. The viewership Ms Yusof gained for her blog would, however, pale in comparison to the numbers she was to attract when she started her Instagram account. It is probable that when visual communication was more the views magnet, she dropped writing. Proudduck was closed some time in the mid-2010s.

She said the name referred to what she and her friends called themselves in school. Why they identified with a fowl is not certain either or if she had used the Malay equivalent, itek back then

When she discovered Instagram, her IG page became the more visual Proudduck (why it can’t transition to IG is not said). Instagram allowed her to be truly visible, to better augment her personal branding and to rigorously market FashionValet. Like so many young women who lead very public lives through their socials, Ms Yusof shows off much minutia of her professional and private life, from the clothes she wears (now only modest fashion) to her many scarves and the 101 ways to wear them to the bags she carries (often luxury) to the posh (probably to her followers) places she has visited, and even to her family life, including photographs of her four children, who are unable to decide for themselves if they, too, desire to live for all to see as their parents. Despite her kids’ very public existence, she told Billion Dollar Moves that she cannot understand why strangers at weddings, for instance, come up to them—unwelcomed—and kiss them on their cheeks.

Researching her backstory on her socials has been a daunting task (we did not want to rely on just one memoir). On Instagram, Ms Yusof has shared 12.2K posts since she joined the site in October 2012 (it is just as large a figure for FashionValet—18K). Not an inconsiderable feat given that she is an oft-self-declared mother and runs an empire-in-the-making, yet has the time to pretty herself for the images she shares. Her first IG post was a photo of a plate of half-eaten nasi lemak. That day alone, she shared five other posts, prelude to how prolific she’d be. And one of them unveiled “a top secret project we’re launching in November”. There was no big reveal and it could not have been FashionValet that went live on 16 November 2010 (nor Duck, which launched in May 2014). In all likelihood, she was recalling the day FashionValet was to launch. Back then, her husband was still identified as “Dean”, as he had been in Proudduck.

Her “best-selling” memoir, published in 2022. File photo: Zhao Xiangji for SOTD

It was a time when FashionValet sold non-modesty fashion, even non-halal cosmetics, such as those by Maybelline. And a time when she shared images of herself without the tudung, Ms Yusof told the BBC in 2015 for a report, “How Muslims Headscarves became a Fashion Empire”, that she adopted the tudung two years earlier, after the birth of her first born. The post of her in a tuding first appeared on IG in February 2013, but she continued to share photos of her with her hair cascading down past her shoulders until at least October of that year, three months after her first son greeted the world. Before that, there was even a photograph of her pregnant self, face covered, baring her distended stomach. On the 4th, she announced on IG: “I’ve made my decision and in Him I put my trust”, effectively denouncing her tube dress-wearing past. From then, she took it upon herself to prove that the tudung can be a fashionable accessory, bearing out what Noor Nabila—sister of Noor Neelofa, who is behind competitor tudung brand Naelofa—said to the BBC, “Nowadays, people who wear the hijab are not from the desert or the village. They can be an icon, be successful, and wear the hijab.”

Vivy Sofina Yusof was born in 1987 in Kuala Lumpur to Yusof Jusoh, a businessman in the construction industry, and Aishah Jelaini (of unspecified profession). She is the younger of two daughters. There is a seven-year gap between she and her older sister, Intan (who, in 2020, was charged for criminal breach of trust, as reported by NST). She told a podcast on Billion Dollar Moves that, because her sister was in boarding school, she was “basically alone” as a young child. “When you are alone, I guess, there is all, like, this creativity coming in your mind, and I love, like, role playing by myself.” She was no longer. Which could have been to her advantage, as she confessed, “I have always been a little bit bossy, so my mom has told me that there’s always been that leadership in me since young. I’ve always been the bossy one, telling the whole family where to eat, what to do, what time to sleep.” It is remarkable that it came to her at such an early age that the bossy self cannot be a solitary pursuit. Yet, she did not think that bossiness does not immediately equal leadership.

In the first year of her Instagram account, Vivy Yusof often shared images of herself without the tudung. Photo: vivyyusof/Instagram

Being bossy is recalled in her memoir The First Decade with upbeat pride. On her kindergarten report card, her teacher wrote: “Vivi needs to learn more patience and be less bossy with her friends.” It was recounted as if to justify her current disposition, which she admitted has not changed much from girlhood, but she did not elucidate if her bossiness comes from her early-year pridefulness or a domineering or overbearing nature, or all three. Now an adult, her response to that unsighted teacher: “Hey, you see bossy, I see a future leader. #selflove.” She even realised way back then that she was destined to be an entrepreneur. “Mom said that when was little,” she wrote, “I loved playing with Lego blocks, building towers from my imagination.” While other kids might grown up to conclude that that was evidence of interest in architecture or engineering, she remember it to have “showed her entrepreneurial interest”. She noted: “Clearly, I had big ambitions for myself.” And her parents seemed to concur. “My childhood made my parents realise that I was going to be an entrepreneur. Either that, or a really bossy person. Both happened. Hee,”

But not much is really known about her childhood other than the precociousness of her own telling. She loved pouring over the book series Sweet Valley Kids—a surprising choice of reading material considering that for most of her foundational education, she went to schools with Malay as the medium of instruction. According to the Malay news site Ilabur, first, Sekolah Kebangsaan Bukit Damansara (Bukit Damansara National School), then Sekolah Seri Puteri and Sekolah Sri Cempaka. On the talk show AmBank BizClub, Ms Yusof explained why she went to several schools (at least two secondary institutions): “I’ve been to so many different schools because I couldn’t stay at one place at one time. I got very restless.” She was academically gifted—most profiles of her described her as a “straight-A student” and she has said that she “excelled” in her studies. How good she was with her education was always exemplified by her taking two major exams in a year: SPM (Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia or the equivalent of the GCE ‘O’-Levels) in Malaysia and the A-Levels in the UK.

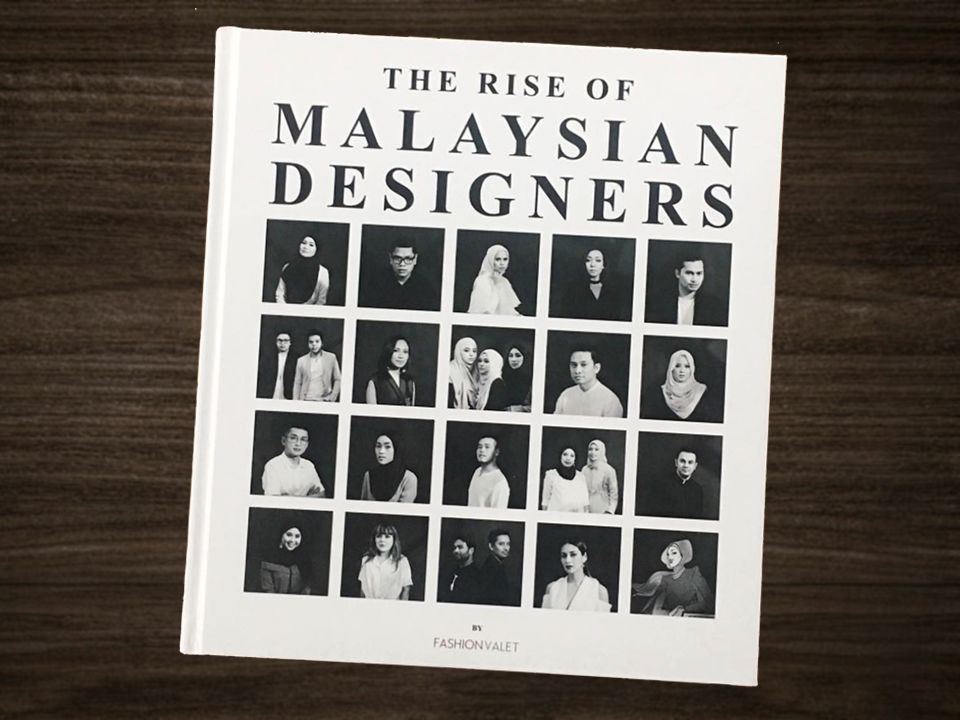

In 2017, published a book to celebrate Malaysian designers. File photo: Hafiz Hazaini for SOTD

After graduating from LSE, she had planned to stay in London with her boyfriend, Fadzarudin Shah Anuar, whom she would marry in 2012. But, work was not easy to find and the couple decided to return to Kuala Lumpur. Before the now-famous epiphany-moment in her boyfriend’s car, which led to the birth of FashionValet, Ms Yusof joined her father’s construction firm for a monthly salary of RM1,500, according to a 2016 NST profile. FashionValet went live in a month from conception, even when her webpage builders told her it would take six. She was not willing to accept that. It was perhaps the drive, coupled with the by-now legendary bossiness, that led to FashionValet’s rapid ascent, which to the placid Malaysian fashion industry back then, was startling. “We were doubling and almost tripling [in sales] year on year, and could not believe it ourselves. It felt too good to be true,” Ms Yusof wrote in The First Decade. Then there was the arrival of competitors too big to silat with.

FashionValet, in 2017, even published a book to champion the brands selling via their platform, The Rise of Malaysian Designers (to mirror the rise of FashionValet?). It was described as a “stunning visual story of twenty designers” (out of at least 400 brands they reportedly carried at one point?). Although the book gave no credit to a writer, it was prefaced by Vivy Yusof (in her memoir, she used the pronoun “we”), which could suggest her second book after her Form Three endeavour. She wrote: “As much as we support international brands, no other feeling can match the pride when we wear one of our own, believe me.” The sales was, as she later wrote, “bad”. Some observers called it a “flop”. The book did not move copies the way The First Decade would years later; it “peaked at about 200 copies”. How FashionValet absorbed the loss was not shared. The nationalistic fervour of The Rise of Malaysian Designers may have underscored Ms Yusof’s conviction in the industry she desired to support, but it was a belated push. The arrival of Zalora in 2012, just two years after FashionValet launched, was to Ms Yusof, “Threat No. 1”.

The publicity material of the third season of the reality TV series that featured the entrepreneurial life of Vivy Yusof. Photo: Astro

Between the fundings FashionValet was seeking—including one presumably from Japan’s Zozotown (Ms Yusof did not mention it in her book, but she did write about going to “their warehouse called Zozobase” prior to clinching the deal) and the nationally-televised reality television MyEG Make the Pitch—Ms Yusof continued to push her own visibility. FashionValet tried to grow the business to compete, as on-line shopping became popular among consumers and business opportunists. But increasing the company profile was crucial. In 2016, she agreed to another reality TV program: Love, Vivy, modelled after E!’s House of DVF (which coincided with the initials of her family members when they were just three). The show ran for three seasons, and it augmented not only her image as a glamorous entrepreneur, but also a capable one. It created the buzz that drove FashionValet’s upward trajectory, forging in viewers’ minds what a worthy-of-more-funding company looked like. It possibly caught the attention of the two organisations that invested in them in 2018 and eventually offloaded them through what has been derisively called a “fire sale”: the wealth sovereign fund Khazanah Nasional and the investment firm Permodalan Nasional Berhad.

Before 2014’s birth of FashionValet’s own brand Duck (which the label preferred as dUCk, but for legibility, we will stick with the clearer Duck), the platform was facing challenges that were partly due to intensifying competition and partly due to their own stock placement model. Ms Yusof shared on The Last Decade: “We were buying outright from designers and brands”, a strategy that is reminiscent of department stores of the ’80s. The outright purchase was an attempt for FashionValet to retain brands, as more were lured by other e-commerce sites—in particular, Zalora—that offered extremely attractive consignment terms, which FashionValet was not able to outdo. However, bought merchandise for a still-scaling business is not tenable. Ms Yusof admitted, “now everyone wanted an outright buy”. Who wouldn’t? No brand would say no to the confirmed sale of their products. But it was not possible that FashionValet could be the stockist with a bottomless pit of funds.

The Duck store in Haji Lane, Singapore. File photo: Awang Sulung for SOTD

The solution to her stocking woes was to start her own label, so that she could control everything, from conception to sales. She quickly realised that the buck is on the Duck. And that FashionValet in the current form is unsustainable. In 2014, after dabbling with wholesale buying from—of all places—Platinum Mall in Bangkok, where, if she thought of it, so did many other Malaysian designers and brands, from Petaling Street to Sungei Wang Plaza, Ms Yusof decided to put out cap sendiri (her own brand). She was certain that the only way forward was with labels she could irrefutably call her own. For someone who had admitted to knowing nothing about fashion, she had placed herself in a dicey situation. Until then, Ms Yusof was a consumer of fashion, even seller, but not, technically, a creator, even if she had collaborated with some of the brands she sold. More pertinently, she had no inkling of garment production and its practices, even if Duck, essentially a tudung brand, required less production fuss. But Duck waddled on. “From that day in 2014,” Ms Yusof wrote in The First Decade, “to 2021, Duck has sold about three million pieces of scarves worldwide.” Five years later, Duck’s success prodded the launch of its sibling label Lilit, the “assessable” modest fashion line.

“I want to be a global brand,” Ms Yusof has frequently said about her “baby” Duck (which became the Duck Group—she has a thing for groups as a single entity). And her first port of call in taking the world was Singapore in 2018. Even her husband had wished it to “be like Louis Vuitton”. That LV is a source of inspiration is interesting: Vivy Yusof is a huge fan of LV, especially their bags. While she has others in her bag storage facility (an image of it was shared on IG), such as those from Dior and, no doubt, Hermès, it has been LV that has a special place in her heart. Such a high-spending customer she has been with LV that in 2016, the brand appointed her as the “first hijabi ‘Friend of Louis Vuitton’ ever” (even the publisher of her book, Penguin, had to wax about it in the publicity material that accompanied the launch). She was only missing a birthday celebration in an LV store. For someone born into affluence, Ms Yusof has a curious predilection to showing her privileged life. But, as the recent scandal regarding the investments in her brands by government-link companies unfolded, Malaysians are now looking at her stash of luxury bags differently, even when the plot has yet to thicken.

“It makes sense that now I am an entrepreneur, I am still the bossy me,” Ms Yusoff had said to the media. But the bossiness was played down considerably when she and her husband had to post an apology on Instagram after the recent controversy flared up. But the casualness of the apology (on social media, no less) had prompted Netizens to call it “insincere”. It is tempting to consider that FashionValet has become so big and well-funded that both founders could not offer a more compelling expression of remorse. On Billion Dollar Moves, Vivy Yusoff said: “Once you get the first investment, you kind of get addicted, and you want to raise again and again… it becomes like a drug that you need, like, raise your valuation.” But she did not say why FashionValet, which eventually closed as the platform it began with in 2022, needed its valuation raised if the company’s corporate governance and fiscal prudence was not, at the same time, elevated. Or why, despite the now-reported five years of loses, she continues to play, on IG, the celebrity she does not want to be.

Update (4 December 2024, 08:00): According to Malaysian media, Vivy Yusof and her husband Fadzaruddin Shah Anuar, co-founders of FashionValet, are expected to appear in court on 5 December to answer to charges of yet-to-be specified criminal wrongdoing. At least one report suggested that the husband and wife were arrested and are out on bail. We are unable to independently established the veracity of the purported arrest.

Illustration (top): Just So