Kanye West was not the first hop-hop star with a big fashion label. It was Sean ‘Diddy’ Combs, recently in the news for allegations of sex trafficking and sexual abuse

A Sean John sweatshirt currently available online at Asos. Photo: Asos

Among the many hip-hop stars with their own fashion brands, Sean John Combs—aka Puff Daddy or P. Diddy or Puffy, or Love (seriously), take your pick—could be considered the biggest, at least back then, when he was enjoying considerable celebrity. In 1998, a year before Jay Z created Rocawear, five before Pharrell Williams conceived Billionaire Boys Club, and 11 before Kanye West established Yeezy (or 21 years before the first Yeezy X Adidas sneaker, the Boost 380, was released), Mr Combs founded his Sean John fashion label and launched it at Bloomingdale’s a year later. In its heydays, the brand was headlining alongside more established names such as Tommy Hilfiger and DKNY, which was astounding because back then, Mr Combs was already accused of sexual assault. It isn’t just the sex trafficking and abuse allegations of the past months that led to the recent Homeland Security raids at two of his properties (which was described by one of his lawyers as a “witch hunt”. Sounds familiar?). He was en route to being the brash and flashy music mogul that he did become.

Mr Combs started in 1990 as an intern at New York’s Uptown Records and then quickly became part of it (interestingly, three of the five in the original team that included Mr Combs have passed away, prompting social media to call the deaths “the Combs Curse”). Three years later, Uptown Records fired him. His boss at the time, Andre Harrell (he died in 2020) told Wall Street Journal in 2014 that “Puff wouldn’t really listen to anybody… so my full time job became managing Puff.” He eventually advised his charge “to go and create his own opportunity”. In 2006, Mr Combs told Oprah Winfrey that he was let go because he “didn’t understand protocol or workplace politics” and also because there could not be “two kings in a castle”. He then set up his own Bad Boy Records (with “support” from Clive Davis of Arista Records, who famously signed the late Whitney Houston to his company), where he became the CEO. Sean John was put out in the market shortly after his first rap album No Way Out was released to rabid acclaim.

A Sean John billboard ad in Times Square, New York, 2011. Photo: Sean Jean/Facebook

Sean John, like Yeezy, got off to a banging start. Both brands were driven more by personality than design, and were largely boosted by the increasingly effective use of hype. In those days, what Sean John offered was termed—if you were already consuming fashion then, you would remember—“urbanwear”. At the time, we did consider this an euphemistic turn of phrase for “streetwear”. Urbanwear is possibly precursor to the offerings of Pharrell Williams at Louis Vuitton; it was a more souped-up take on streetwear, targeted at young inner-city Black men, also referred to, back then, as “urban youths”. While this could be seen as a narrow view, rising brands such as Cross Colors, Fubu, Karl Kani, all started in the ’90s by Black men, including the now-disgraced Russell Simmons (accused of behaviours that have also been levelled at Mr Combs) of Phat Farm, who was founder of Def Jam Records, do frame the scene for us in coherent ways. Hip hop music and, by extension, fashion were providing their audience with what has been described as a “sense of unity”.

And united they were in their appreciation of Sean John, even when Mr Combs personally did not like his brand labelled as ‘urban’. He told The Washington Post in 2016: “I was always insulted by the word; I would get insulted when they put us into [that] classification, because they didn’t do that with other designers.” With his music, he already had a ready fan base, just as Kanye West had when Yeezy was launched. WWD asserted that Sean John “helped define urban fashion”. Mr Combs did not just create an urban visual language, he associated himself with those who appreciated his audible voice. To augment his fashion cred, he debuted Sean John in 1998 at the MAGIC (Men’s Apparel Guild in California) trade show in Las Vegas. And, there was that launch with Bloomingdale’s, a store that, back then, did not carry hip-hop labels (not even already established names such as Cross Colors and Fubu). The Sean John launch was a big deal. Mr Combs recalled to GQ in 2018, “I was greeted by Kal Ruttenstein (Bloomingdale’s late fashion director), a true legend in the fashion industry, and he was wearing Sean John himself. There were cameras and press everywhere and we actually shut down the men’s floor that night.” Mr Combs made another important connection: He found himself in the favour of Vogue’s Anna Wintour.

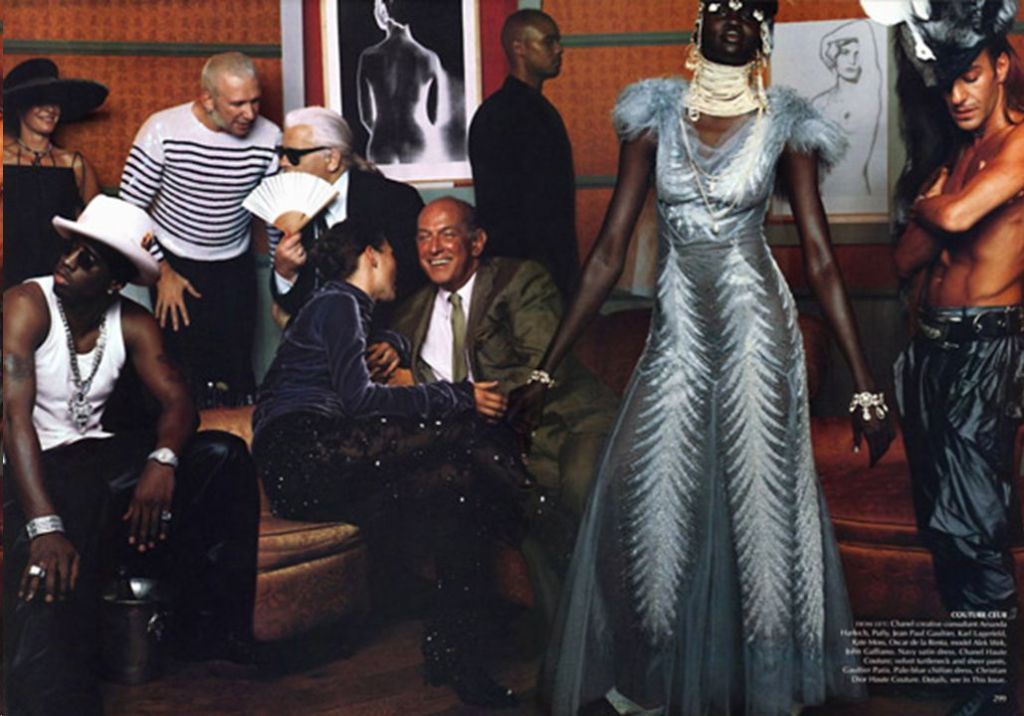

Sean Combs (far left) in a Vogue fashion spread. Photo: Annie Leibovitz/Vogue

In July 1999, Ms Wintour sent photographer Annie Leibovitz to capture Mr Combs in Paris, then supposedly attending the shows during haute couture week. It is not clear why Mr Combs needed to grace what were largely womenswear shows or if the trip came under Vogue’s editorial budget. The pictorial narrative became a 19-page fashion spread ‘Puffy Takes Paris’ (or “How rap’s biggest superstar stormed Paris and the collections”)—styled by Grace Coddington, no less—in the October issue of American Vogue. Hip-hop fashion and bearing have reached, in a major way, the fashion bible. Many till now recall Kate Moss starring opposite the rapper, but it is another image that remained with us: Mr Combs seated to the extreme left of the double-page spread in the company of haute couture’s masters: Jean Paul Gaultier, Karl Lagerfeld, Oscar de la Renta (then designing for Balmain), and John Galliano (before Dior sacked him). The Sean John brand owner, in a white singlet, seemed distant from the action, or an outsider, unable to connect with the clique. Yet, through Anna Wintour, who was beginning to assert her reach beyond couture studios, Sean Combs had arrived.

Sean John debuted their fashion show in 2000 during the autumn/winter season of New York Fashion Week at the events’s old central venue in Bryant Park. It took place, interestingly, after Mr Combs was indicted on weapons-possession charges relating to a shooting at a New York nightclub (although married, he was with then girlfriend Jennifer Lopez, but she was not charged, and he was eventually acquitted). By accounts of those who adored him or wanted to be associated with him, the NYFW show was unadulterated fabulousness. Kal Ruttenstein was one of them, but Cathy Horyn, then with The New York Times, was not. She wrote in the paper, “his clothes, while earning his company impressive profits and the approval of Wall Street, don’t exactly pulsate with genuine fashion news. They are all too often a reprise of current urban looks, updated here with quilted leather, softened there with knits, and supported by his strong accessories.”

A gangsta-style fur coat at the debut Sean John show in 2000. Screen grab: videofashion/YouTube

Many industry folks were indeed skeptical with Mr Combs’s designing ability. In a 2002 report in The New Yorker, the general consensus drawn about his music was that “from the start, Combs was criticized as a mediocre and derivative rapper”. Many in the hip-hop circle consider him “a talent scout, packager, and creator of deals that he has met with true success”. The same could be said of his ‘work’ for Sean John—the results were more styled than designed, an amalgam of ideas that hip-hop desperately desired to express and assert. In a Video Fashion report of that year, Mr Combs enthused: “We are not a hip-hop line because I am a hip-hop artiste. It’s not a celebrity line that I just attach my name to. I design the line, and I also studied it and I know the business.” But Ms Horyn reported that “he doesn’t hide the fact that his line, Sean John, is designed by a professional staff (which once included Public School’s Chao Daoyi and Maxwell Osborne [as intern]), but he’s involved”. This approach would later be adopted by Kanye West.

Mr Combs was perhaps good at creating the image of what a successful music mogul could look like, including the amount of bling that even royalty would shy away from. He was sending out on the runway a caricature of himself: a daddy puffed up with wealth. This was not the thrift-store-gone-high-street enthusiasm of Run DMC; this was ‘ghetto fabulous’ made more fabulous. And, dripping with diamonds or, in Black parlance, ice (at that first show, over US$6 million worth of Fred Leighton diamonds were reportedly used!). As Sean John’s visibility quickly escalated, so did the founder’s confidence (in 2000, he was nominated for best menswear designer CFDA award, but lost to Marc Jacobs): the brand became flashier and flashier in tandem with hip-hop artistes becoming wealthier and wealthier, so much so that Newsweek in 2001 described the Sean John aesthetic as “hip-hop-meets-Liberace”. The flashiness, more often meretricious than not, did help Sean John take in a reported $400 million annual turnover by 2004, also the year Mr Combs finally won CFDA’s Menswear Designer of the Year after four consecutive nominations. The Washington Post wrote in 2016: “He wanted to create fashion—and change the face of the fashion industry”. Sounds familiar?

Sean John store-in-store, Macy’s. Photo: ALKa Creative

A brand may enjoy tremendous publicity and support from Vogue, but for Sean Combs, he wanted more: It has to be made widely available if it were to be truly successful. In 2010, he signed an “exclusive” deal with the US department store Macy’s to sell Sean John offline and online. By 2016, the brand was stocked in 400 of Macy’s 600 stores, according to The Washington Post. It was possible that Sean John was trying to take on Ralph Lauren and similar, to make his label more accessible to more people, especially those who would not walk into the likes of Bloomingdales. SOTD contributor Raiment Young recalls: “When I was in New York in 2001, I went to Macy’s to have a look. Sean John was, I remember, stocked in the same zone as other American brands such as Ralph Lauren. It looked to me like Polo for Black men. Everything seemed bigger, size-wise. Were they nice? Not to me.” Chao Daoyi recalled to GQ, “I remember we were [in the apparel section labeled] ‘young men.’ Then it became ‘urban’—that was the catchphrase. It was only urban because the designers were black. We were doing the same product as Ralph, and Tommy, and Calvin.”

Back in 2001, a first of sort in fashion was scored. The cable TV network E!, together with the now-defunct Style Network (in essence, a spin-off of E!), simulcasted (precursor to livestreamed) a Sean John fashion show during New York Fashion Week (if we remember correctly, it happened only once). Mr Combs said to GQ back then: “Anna [Wintour] told me that we brought back the excitement to fashion week.” I’m 2008, the year he launched a fragrance called ‘I am King’, those million-dollar, celebrity-saturated fashion shows, however, came to a halt (Mr Combs has not explained why he called them off), but it did return five years later. Despite (or perhaps of) his quick success, the fashion-sphere did not take him seriously (with the exception of Donatella Versace, who, repeatedly had him as her front-row guest). Four years after the simulcast, Sean John invested in Zac Posen (the designer shut his label in 2019), making the fashion brand one of the earliest in the US to have a stake in other fashion labels. This was not Mr Combs’s first investment in a brand. Back in 2008, ten years after the birth of Sean John, the company invested in the hip-hop fashion label Enyce. But by 2016, Sean John was losing its appeal, so much so that it needed to be sold to keep the name alive.

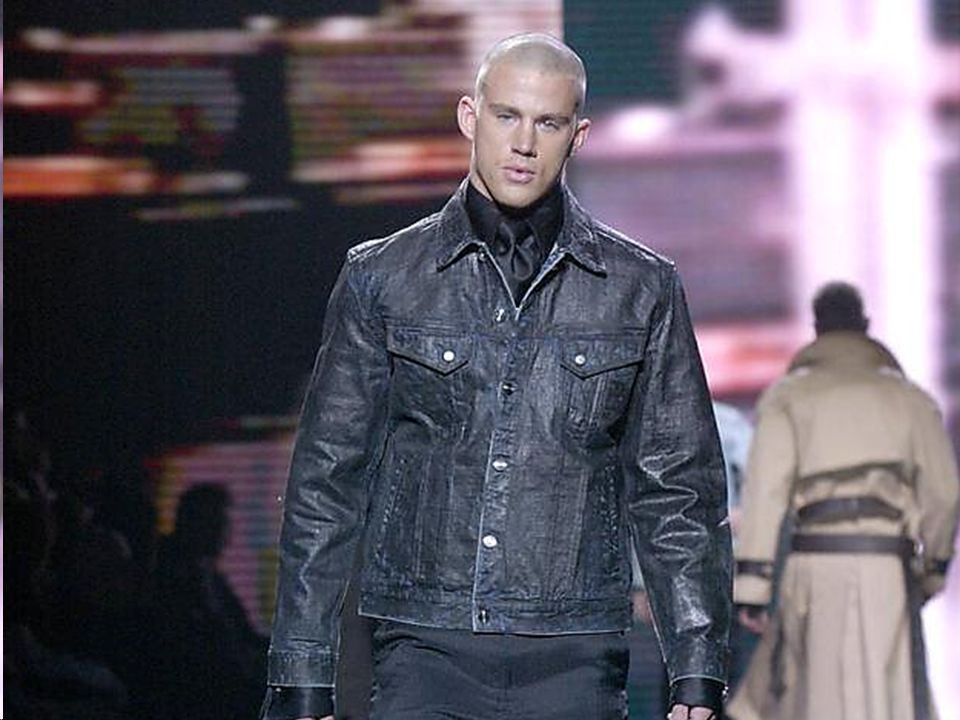

A very young Channing Tatum walking the Sean John show during New York Fashion Week in 2003. Photo: Sean John/Facebook

Global Brands Group (GBG), noted for backing celebrity labels, such as those by Eva Longoria and Jennifer Lopez, took a 90 percent stake in the Sean John, which included Enyce. When the deal was announced, Mr Combs told WWD, “Our new partnership with GBG provides us the opportunity to reach the Millennial customer on a global level, fulfilling its true potential.” That potential, however, was not realised. In 2021, GBG, which was founded by the famed Hong Kong-based garment production and brand management firm Li and Fung, filled for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the US (it was later acquired by Creative Artist Agency [CAA] and became CAA-GBG Global Bran Management Group). A year later, Mr Combs bought back the label he started from GBG for US$7.551 million, as Forbes reported. He told the publication, “I’m ready to reclaim ownership of the brand, build a team of visionary designers and global partners to write the next chapter of Sean John’s legacy.” He did not say how he would revive a brand that, by then and for the most part, had lost much of its bluster and gloat. On the Sean John website, the homepage read: “I got my name back”. It still says that.

In November last year, Mr Combs’s former lover, the singer Cassie (aka Casandra Ventura), filed a suit against the Bad Boy boss for “rape and over a decade of abuse”, as it was reported then. Ms Ventura also accused him of forcing her to have sex with male prostitutes, as well as taking drugs against her will, on top of the other allegations. The day after the suit was filed, both of them settled it privately for an undisclosed sum. Not long after that, Macy’s announced that they were “phasing out” Sean John. A store spokesperson at the time told the media that the decision was part of an “ongoing review”. But speculations at the time suggested that Macy’s was distancing themselves from the sued rapper and that his clothing brand was no longer reaping it in for Macy’s as it once did in the early days. Now that Mr Combs’s reputation is getting more sordid and he is excoriated on social media, following those five lawsuits filed, what is the chance of Sean John making a splashy return? Like Bad Boy, Sean John is not just a brand that Sean Combs built, it is also a personae. In 2002, he told The New Yorker, “I am fashion because I live fashion.” What if he lives hell?

[…] © Style on the Dot […]

LikeLike