A description at the special exhibition Her Kebaya is under scrutiny

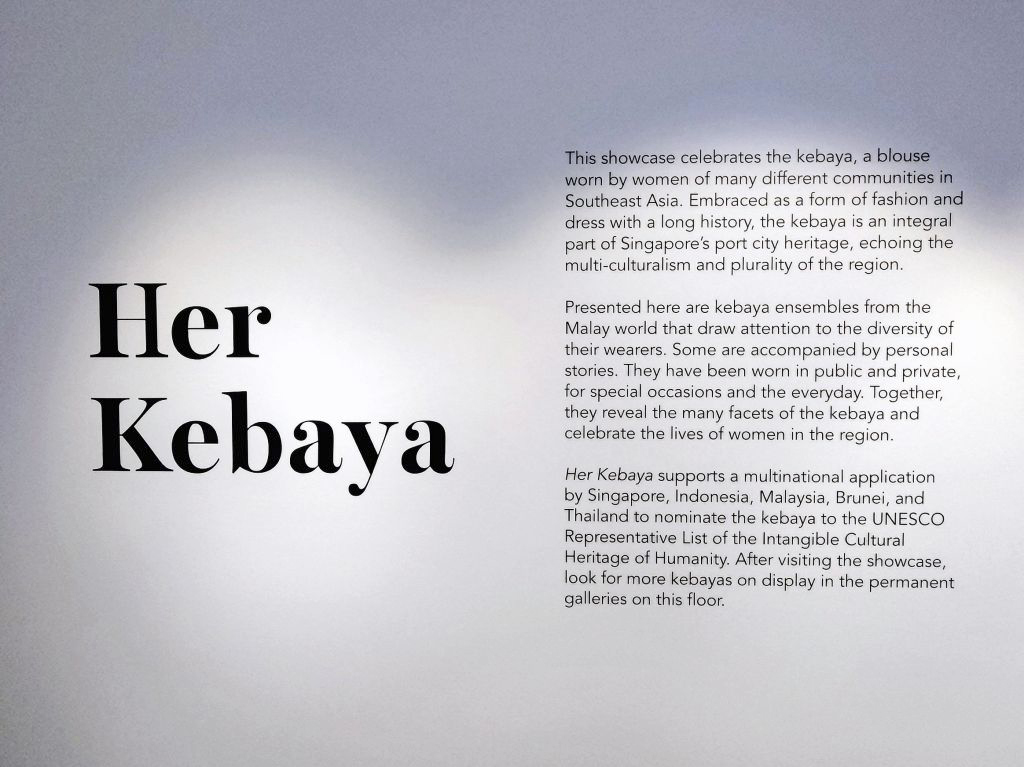

Amendments to a printed description of The Peranakan Museum (TPM) special exhibition Her Kebaya is arousing interest online after Instagrammer Haider Surya Sahle, who describes himself as a triumvirate of “Javanophile, ailurophile, botanophile”, shared images of the exhibition description, comparing one he saw on 1 July and another about two months later. The edited text of the latter removed the declaration that the kebaya is “rooted in the traditional fashion of the Malay-Indonesian world”. In the updated version, the provenance of the kebaya was evaded, stating that it was “worn by women of many different communities in Southeast Asia”. Mr Sahle wrote that the kebaya is “part of Singapore’s Malay heritage” and suggested that the institutions supporting the exhibition (he also hashtagged ACM [Asian Civilisations Museum] and NHB [National Heritage Board]) are “ashamed of this fact.” He demanded to know why TPM had to “amend the text just a month before the exhibition ends.”

Mr Sahle’s IG post was first reported by Wake Up Singapore—“Your Alternative News Source”. For reasons yet to be determined, The Peranakan Museum made those textual changes on the wall facing the exhibits to introduce Her Kebaya. It is not known when those alterations were made. Mr Sahle shared what he discovered on 16 September. Hitherto, it is not certain if the Peranakan Museum saw the IG post and the accompanying comments—some, unnecessarily nasty. It has not responded to the query, nor the growing call for a response. TPM director, Kennie Ting, who also heads ACM and is instrumental in putting together the just-concluded Andrew Gn: Fashioning Singapore and the World, has, similarly remained mum on his own socials, as well as ACM’s (The Peranakan Museum is, according to their website, “a department of ACM”). NHB, too, has not said anything.

The text in question

Although changes were purportedly made to the said text (we do not remember the exact phrasing when we saw the exhibition in June) that appeared in the exhibition, the copy that is shared on TPM’s Facebook page still associates the kebaya with “the Malay and Indonesian world”. This lack of consistency in the communication is rather odd for a museum that aims to encourage visitors “to ask themselves: ‘what is Peranakan?’”. While their primary aim is to present “the cross-cultural art of Peranakan communities in Southeast Asia”, a small exhibition that Her Kebaya is—just 12 exhibits—can hardly embody the ethnic dress “worn by women of many different communities” of this region. It is understandable that the smallish TPM wants to be trans-regional in its study of the culture that has lend its name to the building that houses its splendid artifacts, it’s less comprehensible that the scope of the exhibition has to have a regional voice when it is, in fact, rather limited.

In the catalogue that accompanied the 2022 exhibition A Journey of Singapore Style: 1850—1950 (featuring the sarong kebaya and batiks) at the Fukuoka Art Museum in northeastern Kyushu, the Peranakans were noted to have “fostered their own distinctive culture by forming networks that cross national boundaries”. It also elucidated that “centres of Peranakan population were established in Bangkok and Phuket, Rangoon, Medan and various parts of the Malay Archipelago (the islands between the continental Southeast Asia and Australia)”. The latter ties with TPM’s initial use of the phrase “Malay-Indonesian world”. Given how far the Peranakans have radiated from Malacca or Penang, that description is not inaccurate. The “Malay world”, as historian Lukmanul Hakim of the Universitas Islam Negeri Imam Bonjol Padang wrote in the Journal of Malay Islamic Studies, “is a term that has long been used in foreign literature to refer to a wider region of the archipelago; it even covers most of the Southeast Asian region today.” The Peranakan Museum, although not presenting foreign literature, need not have feared that its use might somehow diminish the breadth of the kebaya’s adoption outside our shores.

The right half of the linear exhibition Her Kebaya

The thing is, Her Kebaya does shine the spotlight on those sarongs and kebayas worn by women here or in Malaysia. The dozen outfits, in a space akin to a corridor, were not only those that belonged to the Peranakans, but also to many Malays, such as the late singer Kartina Dahari, and foreigners too, such as the American songstress of the ’80s Kathy Papas and a Dutch consul’s wife (both women mostly wore their kebayas while living here). The kebayas cover the gamut of styles that were popular among the fashion-conscious of the past, from baju labuh (also known as the baju panjang among the Nonyas here) to the more modern kota baru styles. One striking piece in black (an unusual colour choice as kebayas—especially those worn by the Peranakans—tend to be more colourful) textured cotton that looks quilted from a distance, by one Sadiah bte Mohammad, showed that kebayas need not be body-con to be attractive. The highlight of the show is also the least impressive: an outfit belonging to the ex-president Halimah Yacob: A cotton kebaya labuh, with a tumpal (the ‘cloth head’ in Indonesian, usually with a row of triangles) that, the museum notes, is “in the tradition of the Malay-Indonesian world”.

The curators of Her Kebaya may have overlooked the possibility that the amended text of the introduction to the exhibition would be noticed, hence arousing suspicion of motive. They have yet to state the reason of the alteration or the turning away from “the Malay-Indonesian world”, which could potentially, if unfairly, be seen as a spite of the Malay community. It is not unusual for museums to change their stand on the provenance or history of their exhibits. And it is not unacceptable to include an erratum to the passage that contains the perceived mistakes or oversight. Or, to explain that, in light of additional information or new understanding, they preferred not to narrow the region/areas that their exhibits were ascribed to. Perhaps, The Peranakan Museum was undoing the over-focus on what ACM and its director Mr Ting wildly adores—our “port city”. And the fixation on it. Still, good explanations are always part of the backstories of museum exhibits and, indeed, dress museology.

Photos: Chin Both Kay